-

Author

Aidan Ritchie -

Date

10 Oct 2023

Essay

Angel Numbers on the Dash: Ming Ranginui

Angel Numbers On The Dash is essentially a work taking the piss out of the absurdity of Aotearoa’s housing market. Whilst Ming was working on her idea for the Matarau exhibition at City Art Gallery, she and I had been frantically searching for a rental for 3 months – all throughout the Wellington area. This situation was inspiring for all the most depressing reasons.

We desperately pandered to the whims of apathetic property managers, who seemed to relish the position of power the housing crisis had put them in. Hundreds of people grovelled alongside us to pay $500+ a week towards someone else's mortgage – to live in an ex-state house that hadn’t had a face lift since the 60’s; ironically many of the property managers looked as if they’d had several in that same time.

Fighting tooth and nail for houses that were described as “cute” or “cozy” and as having “lots of character,” but the characteristics they referring to were missing windows and black mold. The absurdity of the situation eventually became comical to us – as a counsellor I see many people who turn to humour when they have been completely desensitized to their situation.

Another thing that I know from working in social services but also as Tangata Whenua is that all notion of hauora begins by having a stable environment. Access to shelter is the bare minimum any person strives for, yet in 2022 Aotearoa owning a home has become a luxury reserved for those with generational wealth or by huge sacrifice. Even occupying a rental is an achievement only attained by subjecting yourself to the degrading and discriminatory process of applying for one.

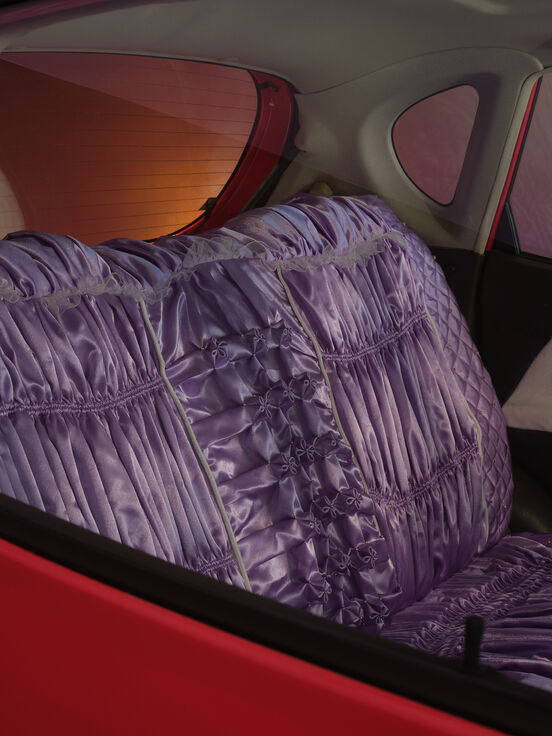

For decades we have been fed narratives from politicians and the wealthy of the lower classes frivolous spending on “avocado toast” and partying. The Daihatsu Ming has pimped out is a commentary on the contrasting comparison between necessity and wealth – where having any access to shelter or privacy has become a luxury. The car, decked out with a chandelier and satin-smocked seat covers makes jest of the notion of someone living a luxurious lifestyle, whilst simultaneously living out of their car.

This theme of people ‘living beyond their means’ speaks to how within a Capitalist society, even paying rent is beyond the means of many. When you find yourself in a society which doesn’t take steps to prevent crises like this, there are often absent yet implicit messages to be read pertaining to the value placed on the population living in these situations.

The Daihastsu has neither a motor or a driver’s seat – which serves as a metaphor for the complete lack of control lower class New Zealand have over their situation. It is impossible to be in the ‘driver's seat’ when your car doesn’t even have one.

One weekend on our way to see Ming’s whānau in Whanganui she noticed a sign outside the Ōtaki Baptist Church which read “Is Jesus your steering wheel? Or your spare tire?”. Ming saw this as a poignant tohu about surrender and faith. Many of Ming’s works tell stories of her resigning herself to blind faith in situations which were beyond her control – in Te Ao Māori we speak of Te Korekore, a realm of darkness, but also one of massive Pō-tential and the place where all life began. The sign raised a good question: Why do we so often turn to spirituality only in times of crisis and darkness? In a situation where your car has no engine, you may as well let “Jesus take the wheel”.

One thing I’ve learned being with Ming is that she gets real spiritual whenever she finds herself in a hard place, and will look for tohu from the world around her as well as forcing me to do improv manifestations. One way that Ming found hope during our search for a home was by noticing the ‘Angel Numbers’ that would frequently appear on the dashboard of my car as we drove to and from house viewings. Hence the title Angel Numbers on the dash.

The gaudy and humorous nature of this work are ways to beautify ugly situations – your eyes are drawn to luxuriously smocked seat and steering wheel, the chandelier, the little cherub praying on the hood; whilst the real story is within the metaphors of contrast, what is absent and what has been repurposed. The Daihatsu may be a beautiful car; but it would be an awful home.

Ming is not one to speak outwardly about the mamae and frustation she has experienced, and offsets the sadness of the pūrakau within her works by making them visually appealing with intricate sewing, cute imagery and humour. However, despite all this, Angel Numbers on the Dash is a wero to those in power and those who have become desensitized to the housing crisis and its impact on the hauora of those who are affected by it.

Ming Ranginui, Angel Numbers on the Dash, 2022.

Ming Ranginui, Angel Numbers on the Dash, 2022.

Ming Ranginui, Angel Numbers on the Dash, 2022. Photographs by Samuel Hartnett.