-

Author

Emma Ng -

Date

28 Sep 2022

Essay

Curator's essay: A Stone, an Echo, a Sign: Aotearoa Jewellery Triennial

‘Climate change better not fuck up my Matariki,’ thinks the character Te Hoia in the opening pages of Coco Solid’s novel How to Loiter in a Turf War (2022). This exhibition is born of the same 21st-century anxiety: how do we hold on to the things our grandparents treasured — their taonga, their ways of seeing, the knowledge they used to navigate the world around them — when that world is changing?

It was a video artwork by Chinese artist Zixuan Guo, shown at ST PAUL St Gallery in 2018, that first stirred this anxiety for me. Lingering shots of the environment around the artist’s hometown are overlaid with a conversation with her grandmother about ‘The Nines of Winter’: a folk narration of the changes to the river, the trees and the birds that follow the winter solstice. What happens when forces like climate change begin to loosen the relationship between the seasons and our ancestors’ common wisdom? Will the tohu we use to navigate our own times change or stay the same? Which lessons are meant to stand the test of time, and which will ebb away in time’s relentless flow?

Makers of jewellery, adornment and other taonga passed from generation to generation are uniquely placed to consider questions like this. Their practices are enduring; the adornment impulse runs indelibly through millennia of human upheaval.

A Stone, an Echo, a Sign suggests that it’s this timeless call to make and remake that allows us to navigate change. Just as oral histories depend on an unbroken chain of speakers — each interpreting the stories for their generation — making and remaking are vital acts of interpretation that keep our inheritances alive by reworking them to meet the present moment.

For Neke Moa (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Ahuriri, Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Tūwharetoa), whose practice is anchored by the Māori concept of taonga tuku iho, this is second nature. Neke and her partner Paula, a tohunga from Taranaki, work together to gather and interpret kōrero atua, the stories of the deities — and the pieces that Neke makes act as connection points for these pūrākau in our daily lives. In this way they are, as Neke titled a previous exhibition, ‘rākau whakarawe — weapons for the everyday’.

Here, Neke and Paula focus on Papaīra, one of the creation sisters in te ao Māori, and some of her eldest children, her tuākana. Papaīra is an ideal guide for this exhibition and the questions it explores. Known for her watchful and curious nature, and for venturing to the edge of the known cosmos and beyond, Papaīra encourages us to look closely at the environment around us — for its rich offerings, and the signs that are embedded throughout te taiao.

Neke collects natural materials from the beach and bush around Ōtaki, working in harmony with their features: the shape of a piece of carbonised wood, or the tapa-like markings on a shell. You could say that the works are partly authored by te taiao, with Neke working to bring out the messages that the materials already carry within themselves.

This idea of an existing language that can be drawn out, or discovered through the process of making, also runs through the work of Moniek Schrijer. The allure of Moniek’s work is that she composes patterns that hint at language, although the satisfaction of full comprehension is always just beyond our grasp. In this exhibition she presents assemblages of stone slabs, glinting synthetic crystals, shells and paint.

This series sees Moniek setting her eclectic materials in large-format copper sheets. They become storage devices, not unlike computer motherboards; prized metals and minerals coming together to supplement human memory. We can appreciate the compositions on a descriptive level — they evoke the wonders of the natural world, from deep geological processes to the fleeting magic of a candy- streaked twilight sky — while accepting that the materials hoard a kind of knowledge that lies beyond our understanding.

Humans form patterns, and patterns form language. Several of the makers in this exhibition reference textile practices, including knitting, lacework and weaving. Within these surviving craft practices, the patterns and processes themselves have come to function as one of humankind’s most enduring storage devices — knowledge kept alive in the echo of hands making the same movements over decades, centuries and millennia.

This idea that craft practices overflow with stored knowledge is not new, and there is a historical relationship between weaving and the dawn of data storage and computer processing. In the 1840s, Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage looked to the punched pattern cards used to instruct Jacquard looms as inspiration for how information and mathematical calculations might be stored in proto-computer programming.

Data, pattern language and textiles converge again in Becky Bliss’s oversized chain links. A lament for the environmental signs we have ignored, the chain maps global temperature increases since 1900 — its colour shifting from blue to a deep, bruising red. The work uses a data set from the University of Reading. Becky’s interpretation works the data into a gridded form inspired by the warps and wefts of weaving, with Becky noting that textiles were one of the first industries to be mechanised during the industrial revolution. It was not long after this that signs of the impact of our growing reliance on fossil fuels began to appear in our environment.

It is tempting to see this work as a kind of mourning jewellery for the earth. But the opportunity for us to make and remake our world is never done. The final section of chain is based on projections for our current decade, reminding us that our fate is not yet sealed. Storing within it 130 years of data, the chain encourages us to contemplate the human impact that additional lengths might record, and the story it will tell future generations about our actions.

Rowan Panther’s practice of Moana lacemaking is also used as a way to record her particular position in time and space. As a maker who studies museum collections in the process of creating her work, Rowan wanted to produce a series that acts as a personal collection — indexing some of her own influences and the environment that surrounds her when she is at home in Northland.

The works in this Kohumaru Collection use a technique called gimpwork, in which motifs are picked out using a thicker thread. Here, the gimp motifs are kawakawa, kauri and pōhuehue leaves, inspired by samples she picked from her lush Northland surrounds. She bypasses drawing in her process, instead interpreting the samples directly into lacework patterns — bringing the work into direct conversation with the place in which it’s made.

Rowan’s use of muka, a fibre she makes from harakeke, supports this direct relationship with place. The works function as relational objects — new interpretations born of many influences — also holding within them connections to Rowan’s English/Irish lineage and Sāmoan whakapapa through the practices of lacemaking and Moana Oceania adornment.

A similar, multistranded conversation is carried out in Shelley Norton’s long, warping necklaces. Knitted in intarsia from shreds of plastic bags, Shelley follows the breadcrumb trail left by another artist — the painter Frances Hodgkins — a century ago. She focuses on three paintings Hodgkins called ‘self-portraits’, which in fact depict tight constellations of garments and everyday objects. Cutting her own path of curiosity and interpretation through these paintings, Shelley knits her way around them at a 1:1 scale — creating a kind of echo portrait that seeks out Hodgkins’s ciphers.

The necklaces are accompanied by flat works, formed by melting together small fragments of plastic to recreate selected objects from the Hodgkins self-portraits. These can be worn as brooches, earrings or other personal adornments — in turn becoming carefully chosen props for their wearer’s play with self- representation. In this way they enter into conversation with Shelley Norton and Frances Hodgkins across time, space and medium.

Of Hodgkins’ ciphers, Shelley says: ‘I want to take them for a walk into the jewellery realm, to put them back on the body, to enhance and support gesture, add volume to the silence of body language.’ Like the other makers in this exhibition, Shelley reaches for a language that eludes speech — a language that can only be recovered through jewellery.

Of course, it isn’t just humans who create pattern languages. The inscriptions left by te taiao on the shells in Neke’s pieces and the mineral veins that pulse through the slabs of pounamu and ribbonstone in Moniek’s work tell us this. The natural world has its own ways of speaking.

Raewyn Walsh wades into the conversation with her mimicry and disruption of nature’s patterns. Here she works with a new material: beeswax collected from the hives in her backyard. The wax supply is seasonal, limited and already expertly worked into perfect form by the bees themselves, who demand recognition as accomplished makers in their own right.

Combining the beeswax with pigment, damar crystals and essential oils, Raewyn reworks it into hollow pendants formed by the shape of her hands. Like many of Raewyn’s previous bodies of work, the pendants test the balance of the relationship between humans and the natural world. They call to our sometimes disquieting human urges and encourage us to recognise ourselves as interdependent parts of the ecosystems that surround us. They shrink us down into fellow agents of the world, alongside the bees.

Raewyn, like others in this show, reminds us of how much we don’t know — how much remains beyond the tip of our tongue. Some secrets are held tight by the bees, by te taiao, by the atua. There are pattern languages we will never decipher and never fully understand, and some we can experience but not articulate. But we can remain like Papaīra, alert and curious. Many of the works in this exhibition have taken countless hours to make. For some of the makers these are hours filled with walking, looking, thinking and collecting. Even when hands and tools are working, there is thinking.

So — how do we hold on to the things our grandparents treasured, as the world changes? This exhibition suggests that, to keep our inheritances alive, we have to continually reinterpret them for our times. Just as the muka cord of a hei tiki eventually wears away, we must accept that some things will need to be remade — but the worn cord leaves an impression in the pounamu, a pattern of wear that becomes an important part of the story. It is through making and remaking that we weave ourselves into the big fabric of time and place, which extends far beyond our own lifetimes.

—

This essay was published to accompany A Stone, an Echo, a Sign: Aotearoa Jewellery Triennial, curated by Emma Ng with exhibition design by Micheal McCabe, and presented with MAKERS 101.

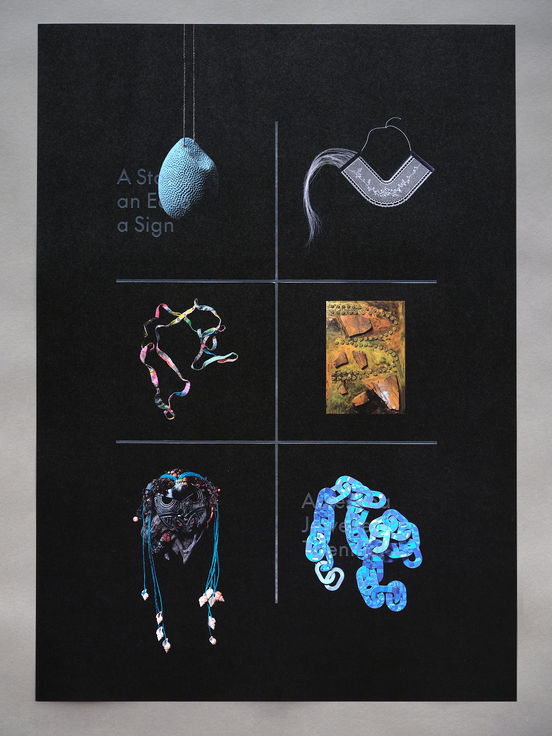

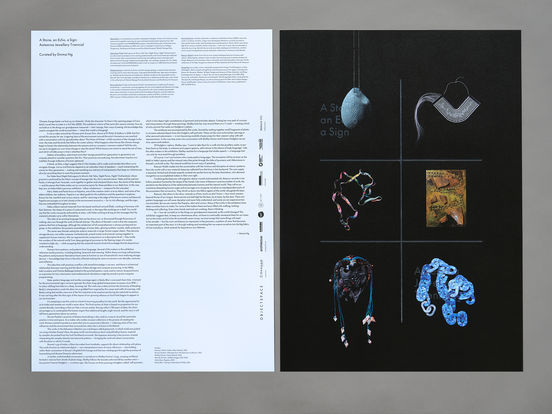

Tear-off poster for A Stone, an Echo, a Sign, featuring works by the exhibiting jewellers

Raewyn Walsh, Hollow Wear (detail), 2022

Rowan Panther, Pohuehue from The Kohumaru Collection, 2022

Shelley Norton, Props (detail), 2022

Moniek Schrijer, Golden Nugget, 2021-2022

Neke Moa, Papalau, 2022

Becky Bliss, Casting a shade (detail 1900), 2022. All photographs by Samuel Hartnett.

Tears-off for A Stone, an Echo, a Sign featuring essay by curator Emma Ng