-

Author

Jane Groufsky -

Date

6 Apr 2023

Essay

Essay: Cook & Company

The brooch has no control over its fate. Not so long ago, it was sheets of acrylic and sterling silver: cut, inlaid, pinned and now transformed. After a brief moment in the gallery spotlight, where to next? Perhaps it is presented as a gift, to be stored in a jangle of costume jewellery – beloved, eliciting admiration every time it is worn, and gently tarnishing over time. Or perhaps it is selected as a new acquisition for a public institution. The brooch would be fastidiously conveyed to its new home and nested between a Warwick Freeman necklace and a Kobi Bosshard bangle. It is dark and quiet there. Can it sense the drawers full of hei tiki and ‘ulafala in the storerooms down the hall?

Making contemporary jewellery is a protracted and meditative process, offering plenty of time for contemplation about how a piece will be received in the world once it leaves the jeweller’s bench. It is not enough for Octavia Cook to simply usher a piece of jewellery into existence: she is enthralled by the possible life it could lead as an object that is worn, treasured, lost, displayed, stored, gifted or forgotten. Throughout her career, Cook has explored the dual existence of contemporary jewellery as public objects which offer a glimpse into the private inclinations of the wearer. In reuniting works from past and present collections for our viewing in the exhibition Cook & Company, the barrier between public and private is briefly lifted.

Cook & Company builds on the legacy of the jeweller’s ‘Cook & Co’ era – work created under her expansive, fictional company that was active from 2002 until its destruction in 2011 (in an aptly titled exhibition called Coup de grâce). This time, ‘company’ encompasses the community she has built up over the 25 years of her jewellery career thus far: the contemporaries in her field whose work she has collected; the commissioners and institutions who have supported her; and the new connections she has formed through the commission of jewellery storage systems from other practitioners. Cook & Company is also a family reunion for her own work. Private commissions and publicly owned pieces meet, many for the first time, to build a picture of Cook’s long-held interests and sensibilities.

—

When considering the way the personal and public intersect in the works of Cook & Company, an easy place to start is with Octavia Cook herself. Much of Cook’s oeuvre, particularly that made under the Cook & Co label, saw her relishing in the potential of her own name. The easily interlocked letters C, O, O and K demanded to be incorporated into a chain, and the octopus was a natural mascot for someone named Octavia. An octal numeric system underlies the Cookiverse and eights are inescapable in Cook’s practice – even now to the number of letters in her latest series, I.M.P.O.S.T.E.R. (2022). Although Cook claims to have removed herself from her own work recently, hints of her biography still come through. R (Rock) in I.M.P.O.S.T.E.R. depicts the guano-and-sea-slime-encrusted rock formations on the shoreline of Karitāne where Cook often walks with her family. A brooch in an earlier acrostic series, S.H.A.L.L.O.W. (2020–21), was even more personal, illustrating moles from her husband, her son and herself.

These associations from the maker are subtle. As wearers, we also make choices about what we want to reveal of ourselves and what we want to keep private. The essentially decorative function of most jewellery puts individual taste on display, inviting positive interactions but also potential judgement. And our taste, knowingly or unknowingly, is shaped by established systems and signs which foster desirability. Cook deliberately engages with these forces, and her work has always been in a dialogue with the historic canon of jewellery, though the precise forms this dialogue takes fluctuate in overtness and subtlety. Her cameos, the bread and butter of her commissioned work, are easily read in this context; other forays into traditional forms go a little deeper into jewellery history. Cook’s Ancestral Home & Garage (Pakuranga) and An Inheritance of Monumental Sentiment (both 2009) continue the tradition of Grand Tour micromosaic jewellery, in which depictions of classical landmarks became wearable high-end souvenirs. Cook borrows the technique to illustrate her childhood home in Auckland with the same reverence as she does the Taj Mahal. Another continued fascination is the Georgian and Victorian tradition of acrostic jewellery. Abstract R.E.G.A.R.D. Pendant (2012) is Cook’s earliest work of this nature – here the traditional gems (ruby, emerald, garnet, amethyst, ruby and diamond) have been rendered as an acrylic tesserae border around a miniature eye.

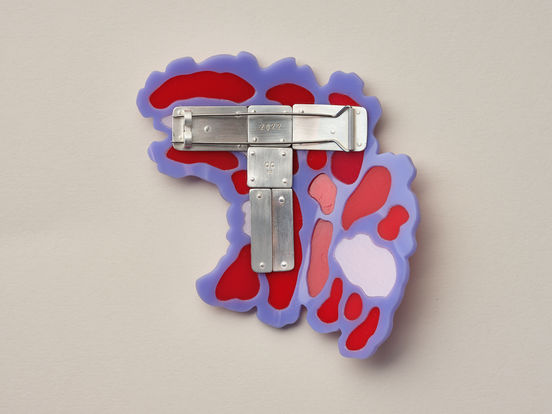

The acrostic has taken an idiosyncratic turn in Cook’s I.M.P.O.S.T.E.R. series, moving even further from sentiments which would’ve been familiar to Victorian audiences. For I.M.P.O.S.T.E.R. – a series consisting of I (Immortal); M (Mermaid); P (Parasite); O (Owl); S (Seaslug); T (Turkey); E (Emperor); and R (Rock) – Cook supplements her favoured acrylic with wood and shell, tightly inlaying the disparate materials and colours to illustrate zoomed-in fragments of her chosen species. According to Cook, I.M.P.O.S.T.E.R. is not a reference to the inferiority complex ‘imposter syndrome’, but instead an exploration of how jewellery can be used like strategic colouration in nature, to blend in, attract or repel. Just as the emperor moth depicted in E (Emperor) mimics the furious gaze of the owl to scare off predators, wearing Cook’s jewellery lets you shape your experience of the world. The pieces are sizeable, allowing them to more easily enact this transformation. As Cook says, “statement jewellery is not for the faint-hearted – if you step out of the house wearing it you need to be prepared to be seen or have others interact with you about it”.

With I.M.P.O.S.T.E.R., Cook is testing theories of what will continue to appeal to her audience and challenging what we find desirable. The turkey wattle is not known for its attractiveness; if anything, it calls to mind associations of the derogatory condition ‘turkey neck’. Cook’s T (Turkey) seamlessly embeds globules of red and pearlescent pink acrylic into a lilac ground and features an inventive sterling silver back. Can the act of transforming a piece of turkey skin into jewellery bestow value on it?

Equally, Cook examines how far she can push conventional decorative motifs taken from nature. Butterflies naturally lend themselves to ornamentation and have long been used as such. Does this appeal remain in place for their less flashy cousin, the moth? Can homing in on the butterfly-like jewel tones of the parasitic wasp of P (Parasite) overcome our natural revulsion towards their species?

—

Covetousness – the need to have and to hoard – is a quality inherently connected to value. Cook recalls her childhood visits to museums and galleries and her sheer urge to possess certain objects on display; she would challenge herself to pick just one object from each gallery to own. This compulsion to possess leads to the other life of jewellery when not on view and is another consideration behind Cook & Company. The way we choose to keep our treasured items safe is as personal and revealing as the practice of collecting itself. When inviting seven contemporary multidisciplinary makers to consider this idea, Cook kept her brief deliberately open to interpretation: “some kind of system – in their own aesthetic and material choice – able to house a collection of jewellery or precious objects/taonga”.

The resulting works touch on different facets of the relationship between jewellery and the home. A dollhouse, designed by Nicholas Stevens and Deborah Smith and constructed by Emile Drescher, calls to mind domesticity. It is not solely market value which makes its potential contents precious, but the sentimentality that we attach to them. And Anna Wallis’ little shelves are a continuation of the materiality of her own jewellery practice – a sculptural solution that maintains the decorative function of jewellery even inside the home.

With all of our precious things, we make decisions that balance use with preservation. Some of Cook’s works in Cook & Company, like the pieces on loan from Te Papa and the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, have found themselves at the extreme end of this spectrum. Works acquired for public collections are in it for the long haul, with those institutions’ stated goal to keep the objects safe in perpetuity. This means a life spent mostly in the dark, making brief cameos on the gallery floor for a show such as this one.

Conversely, McLeavey 40th Anniversary ring makes no secret of its time as a worn and cherished object. Commissioned in 2009, the ring was returned to Cook in 2014 after one of the swan’s heads came off with wear. Cook replaced the missing area with 18 carat gold and a champagne diamond eye, following the kintsugi practice of embracing a perceived flaw. Such accidental damage is unusual for Cook’s work, however. She makes pieces to last and avoids the ephemeral, instead using materials like tough and long-lasting “heirloom plastics” (the antithesis of the reviled ‘single-use plastic’). These works are equally treasured whether they depict a sea slug or a lovingly rendered portrayal of a late pet.

If you were to pick up M (Mermaid) and turn it over, you would discover the mellow sheen of mother-of-pearl shell. Contrary to the usual orientation of decorative jewellery, it is the face of the brooch that features the rough, dark, outer side of the shell. Cook isn’t depicting a storybook mermaid, but a scaly, realistic creature of the deep. The mollusc the shell comes from wants to keep the iridescent side of its home to itself and Cook offers the same opportunity to the brooch’s future owner. Cook’s career-long fascination with the public and private, the personal and the impersonal, is ingrained in her pieces. Even when worn in public, this brooch keeps a secret. The wearer can decide whether to reveal the invisible detail to admirers – the inevitable ‘public interaction’ Cook counsels they be prepared for – or to keep it concealed. In creating objects that present this choice, Cook’s work responds to our deep-seated personal preferences about how much of ourselves we share with the world.

—

Jane Groufsky is Curator of Social History at Auckland Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira and a member of the Objectspace board. Her research returns to the way social history can be read through textiles and adornment, and what these crafts reveal about the attitudes and values of an era.

—

This essay was published to accompany Cook & Company.

Octavia Cook, I.M.P.O.S.T.E.R. brooches, 2022

Octavia Cook, M (Mermaid). 2022

Octavia Cook, S (Seaslug), 2022

Octavia Cook, R (Rock), 2022.

Octavia Cook, T (Turkey), 2022

Octavia Cook, I (Immortal), 2022

Tear-off for Cook & Company