-

Author

Bronwyn Lloyd -

Date

11 Aug 2022

Interview

Interview with Christopher Duncan

On More than Castles and the language of weaving

Bronwyn Lloyd visited Christopher Duncan’s studio in central Tāmaki Makaurau recently to talk to him about his exhibition of contemporary flatweave rugs, More than Castles, currently showing in the Cemac Foyer at Objectspace until 21 August.

—

BL: The title of your exhibition is intriguing, Christopher. Does it relate to your idea about rugs as the clothing of architecture?

CD: That was about historical tapestries and other kinds of textiles hanging on the walls in castles and estates. The reason the show is called More than Castles is because I came across a quote in an article I was reading online about the 16th century tapestry, The Lady and the Unicorn in the Musée de Cluny in Paris. The writer pointed out that to commission a piece like that at that time would have cost more than the dwelling in which the tapestry was to be housed, which, even by today’s standards, is a remarkable idea.

If I were the type of person who was buying millions of dollars worth of art, it’s still likely that my house would cost more than a Damien Hirst formaldehyde shark. If I bought one of those I’d have a massive mansion somewhere that would still trump his work, you know. But in the middle ages, no, The Lady and the Unicornwas worth more than the castle. I thought that was an interesting idea because we live in a different time now and our relationship to textiles has changed.

BL: Is part of the impulse behind More than Castles the desire to assert that rugs are more than decoration?

CD: Rugs would have been utilitarian objects in the beginning, tent walls, seats, partitions, bags, saddles – a key part of daily life, as textiles are now. We just don’t see them like that. People forget that their curtains and their teatowels and their sheets were all woven, not by hand anymore, but woven nonetheless.

BL: What came across in your written statement for More than Castles was the way that when you are looking at old flat weave rugs you can see the story of their making. You can see the moment a weaver had to pack up their loom in the middle of a piece and the place where they’ve taken up the work again. You’ve trained your eye so that you can read all of that history in the piece. That’s an amazing skill. When did you realise that you’d become that kind of reader?

CD: Part of the process of teaching myself to weave was challenging myself to look at a textile and think, how was it made, can I tell? Who made it was not necessary to know, but the question of how they made it was. I bought this rug from Babelogue recently (gestures towards a rug on the sofa). You can see how the pattern is wonky and the parts don’t align and bits are all over the place.

BL: But only you would see that.

CD: Yeah, but if you look at a rug and think, oh it has a pattern so it must be even and perfect, but then you notice that this one isn’t, you naturally ask why is that? It was definitely woven on the move. When the weaver relocated it and retensioned the loom, suddenly this design element here would have been lower than it was before, but they would have had to keep building it up, keep going. And here they started a triangle or point and then they thought, no I’ve got to begin the starburst, immediately! Crazy!

BL: Let’s pick up on the point about your being self-taught. In your practice it seems as if this is liberating – that there is freedom in being able to make your own way and take your own approach to weaving. Is that the case?

CD: Teaching myself, I think, was a good thing. I didn’t really have any other options and I was happy trucking along with making mistakes. I remember there was a period where it was even difficult to throw the shuttle from left to right because my warp was all over the place. My goal at that time was to be able to weave relatively unhindered by my mistakes. That took a while to iron out. For example, one basic thing I learned was that when you make a warp, especially a long one, you can’t use a variety of different yarns. You can use several colours of the same type of yarn, but you can’t use jute, or muka with a fine wool, for instance. It’s okay for half a metre, or even a metre, but then after that it’s just diabolical. Every fibre needs different tensions, and when I started I didn’t realise that and I had warps that were a massive fail because of it. It was a nightmare.

BL: So when you had those fails, were you derailed or spurred on?

CD: They spurred me on at the time. They just opened up another enquiry that I had to try and answer. I’d pore through forums online trying to find someone who might have mentioned the issue I was having, or explain what might be going on. You could post there as well.

BL: And that helped you resolve some of the technical problems you were having?

CD: It did, even though sometimes I didn’t have the words to describe what I was doing wrong or people couldn’t quite understand where I was coming from. I got there in the end.

At a certain point I started to understand more about the physics of weaving and more often than not there wasn’t one fix. It was a multitiude of small things that I was doing ever so slightly wrong, which were cumulatively causing a big problem.

BL: Now that you’re further along in your learning, I imagine there are fewer of those problems to deal with. Do you place new challenges in your way now, like working with new materials, or introducing a new form into your practice like the flatweave rug?

CD: Yes, I used a simple frame loom to construct the rugs for More than Castles, and the simplicity of the loom enabled me to work with the personality of the warp. Inconsistency and unique characteristics become texture and conversation between yarn.

BL: Are your problem solving skills something you developed in your earlier career in fashion design? Do you revel in complex problem solving situations?

CD: I guess so, but I don’t love everything complex about it. I don’t design my own structures or anything, like twill, or jacquard. Maybe I will one day, but that never really interested me so much, and yet in some way I am designing structures a little bit.

BL: Some weavers really delight in drawing up exhaustive plans and structures that they then have to replicate on the loom, but is your method to have a concept for a piece rather than a set plan in mind when you undertake a work?

CD: Yes, the first 50-70cm of a piece sets up what the rest of the piece will look like. For example, the piece I’m working on at the moment is in natural tones. I wouldn’t suddenly now put blue in, or make the last metre of it blue.

There’s a level of spontaneity to it, but within bounds. I’m trying to train my brain not to interfere. Sometimes I’m there weaving and I’m constantly changing structures and yarns that I’ve chosen to work with, quite intuitively, and then my brain says, “what’s going to come next?” Then I think, why am I stressing out about what’s coming next?

It highlights our relationship with how we panic about the future and fret about the past. I didn’t need to second-guess myself for the last metre-and-a-half that I’ve woven, but suddenly in this split second my brain’s interfering and saying, “what’s happning now?’.

It doesn’t matter!

BL: In a way, it’s a template for how you can apply that thinking to other aspects of your life. Is that how you see weaving?

CD: Yes, more and more. I like to read a lot about Eastern philosophy, Chinese thinking, the Dao de Jing, the I Ching, and other texts like that – it always comes back to the Yin and Yang relationship within the world. Alan Watts uses weaving as a metaphor for that same kind of idea of the warp and weft passing over and under each other and how they are completely inseparable.

BL: You have described the way that when you are weaving you get this sense of falling into time and recognising that you are part of a continuum of makers.

CD: Yes, in a way it’s something like the way we think about ancestral lines. You know you come from thousands and millions of coital relationships, right back to bacteria. We know this but we can’t really fathom it or understand what that means. We just know we’re part of it. When you learn a craft, or apply yourself to something, you do become part of that lineage of thought. Sometimes it’s a blood lineage, sometimes it’s a cultural one.

BL: I admire the way you pursue your own direction as an independent weaver, learning as you go and experimenting with the possibilities of this craft. Where do you find your points of connection with the wider textile community?

CD: I made those connections years ago. Doris de Pont has been really helpful. She put together a group exhibition of weaving at Objectspace in 2015 called Strands: Weaving a New Fabric. A lot of us met each other through that exhibition and have remained friends since. I met my friend Rachel Long then and Patricia Bosshard. I’ve spent a lot of time with Patricia and Kobi since then, which has been so special.

BL: That’s amazing to hear, and it demonstrates the value of really well considered group textile exhibitions as a platform for creating connections among makers.

CD: It does. Another valuable connection I made was when I was researching Robin Brandt’s collection of flatweave rugs out in Oratia. In my own weaving I’ve always wanted to put in random little motifs and things. I didn’t know where this impulse came from, but then I started looking at all these old rugs and saw that those weavers were doing it too. Often they do it with that kind of Superman ‘S’ shape. They would have a pattern, but then suddenly they’d put an S in here, and one in there. I saw a rug where one particular weaver had gone crazy with the S’s and put them everywhere, and I thought, what’s that about? Is it a signature, or something they just feel like putting in? And then I thought, oh, that’s much the same as when I insert my motifs. A weaving impulse of a kind – almost an instinctive response where the brain says, “I’m bored, it needs something”.

BL That’s quite a revelation Christopher. So up until then you hadn’t really interrogated that impulse in your practice?

CD: No, I just felt it was necessary. Some of my early work was very much about those motifs. I did lots of squares and crosses and I’d put them in like movements throughout the work, but I’ve peeled away from that more recently.

BL: I love this idea of a secret code, a secret mark, the idea that maybe there’s something in the weaver’s DNA that compels them to add these motifs.

CD: I do too, but in a practical sense, you do end up focusing on one area a lot in weaving, or on a progression that’s so absorbing, so maybe it’s the brain’s reaction against that monotony. Maybe the brain is actually saying, I’ll put a big red line in, but you end up compromising by putting in a little black square instead.

With traditional flatweave rugs there would have been a set of rules or cultural expectations that certain shapes and colours would be used in a rug design, and of course they did their own dyeing, so there were restrictions in the colours available too. Perhaps putting your little shape in where it shouldn’t be, or where you think it offsets the work, was a mini rebellion. Isn’t that what lots of artists do as a way of creating tension?

BL: Talking with you reminds me how important it is that we become more attentive to detail, so that we can learn to see all these stories embedded in textiles.

CD: I do feel like it’s a language, but I don’t really know what it says to me. I like to read it though. It’s like when we listen to music without vocals that we can interpret, and yet we still find something in it. Can we look at textiles the same way? Maybe that’s what we’re missing a little.

BL: Your work is about the reward that comes from scrutinising something really intensely, and it’s also about the delight in materiality, pattern and texture, and how when we look at a textile, and when we touch it, we form a relationship with it and the story it tells.

More than Castles is a delight. Thank you.

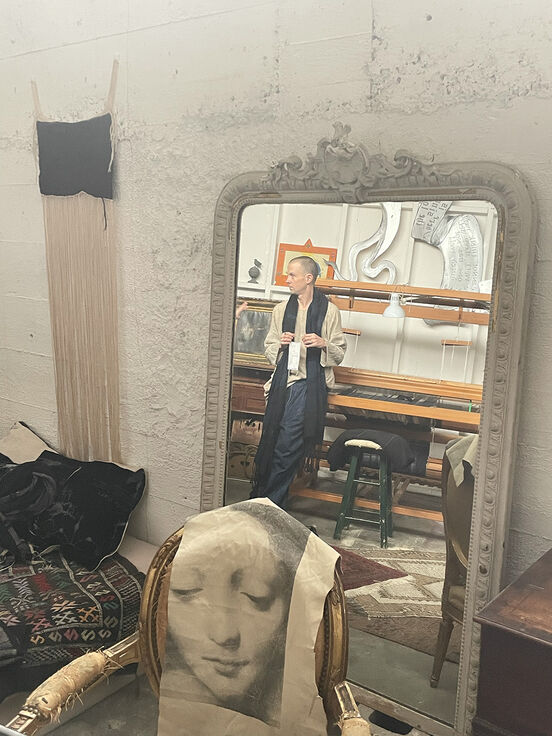

Photographs taken at Christopher's Cross St studio

Phase one of Christopher Duncan's exhibition More than Castles in our Cemac Foyer

Phase two of More than Castles

More than Castles installed at The National in Ōtautahi. Photograph by Sarah Rowlands. Courtesy of The National.