Interview with Sione Faletau

Sione Faletau: I’m of Tongan descent, my father comes from the villages of Taunga, Vava‘u, and my mother is from Lakepa, Tongatapu.

I’m based in Tāmaki Makaurau, Ōtara. I’m a multi-disciplinary artist and my practice has centred on performance but due to the restrictions of Covid-19 I recently moved into an audio-digital practice. I moved to this way of working because of the limited interactions and access I could have with public spaces and audiences, but I have continued developing this way of working after restrictions lifted.

Objectspace: Tell us about your work for Toro Whakaara.

SF: I was drawn to ideas around the notion of place and how we interact with place for this exhibition. My inspiration first came from the paintings of Fatu Feu‘u, his Tatutai Matagofie works that depict local landmarks. These paintings really intrigued me because of the narratives Feu‘u included in these works, particularly relating to the Manukau Harbour. As I researched more about the Manukau Harbour I found out about the Orpheus shipwreck, the worst maritime disaster in New Zealand’s history, where the ship ran into a sand bar in the harbour. This got me thinking about forms in the environment that are naturally hostile and the harshness of the moana – how the moana is a barrier, but also connects us. It’s a lifesustaining entity but we are always at its mercy.

I looked into other times where navigation across the moana was impacted by these naturally hostile forms. There was a group of Tongan men that left for Aotearoa for boxing and employment opportunities and during their journey they ran aground on the Minerva reef. They were marooned there for over 100 days. They eventually built a raft from pieces of previous wrecks and some set off for Fiji for help. This is a story that is told in Tonga about survival and resilience, but I wanted to think about the role the natural environment played in this story too.

In the exhibition I’m using the architecture of the space to talk about how we navigate around physical obstacles or how these forms overcome us, to create a relationship to these talanoa, the telling of these stories.

OS: You use sound to evoke a representation of site in your work and song as a conduit for transmitting intergenerational knowledge, something that can traverse time and space.

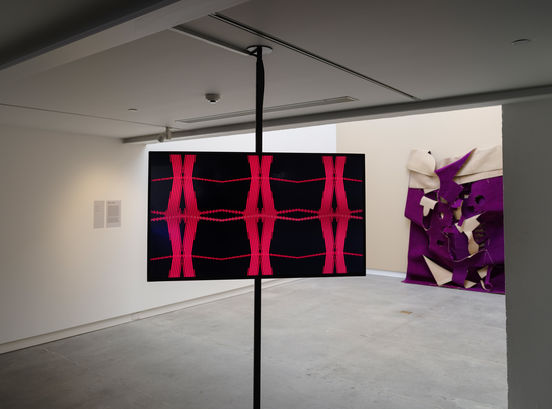

SF: I’ve always been dealing with sound in my works and when I transitioned into a more digital way of working I wanted to create a way where I could give a visual representation to sound. I wanted to translate sound to a visual form of talanoa. I started recording sounds at different sites, some naturally occurring sounds, like wind, and other sounds like song or musical instruments. I developed a way of taking the sound wave data and audio wave spectrums and use kupesi patterns to manifest digitally rendered shapes that gave the sound a visual form.

In Tongan culture the word for sound, ongo, has two meanings. It relates to both sound, but also to feeling. This relationship between sound and feeling is integral to my work – these sensory entities are inseparable. Through feeling you create sound and through sound you create feeling.

I see how our ancestors extracted things from nature to communicate meaning – like kupesi. I want to be able to create a new way of extracting forms from nature to create something that relates to Tongan tradition, that’s meaningful to me. These are my physical and visual representations of talanoa.

OS: The exhibition was catalysed by the idea of hostile architecture. This provocation suggests that our experience of the built environment and place, can be fraught – in a state of tension that prioritises some people’s needs over others’, and at odds with the natural world. What experiences do you have of hostile architecture in your daily life?

SF: I was introduced to the idea of ‘hostile architecture’ through working on this exhibition and now I understand this concept, it’s been hard not to see it everywhere. I’ve been thinking most specifically about an old brick bus stop that was down the street from me when I was growing up. We used to shelter in the bus stop on the way to school, it was warm and cosy and we could hide in there as it blocked off the elements. In 2012 they replaced it with a new modern shelter – it was glass and had a little roof but didn’t give the same respite for people from the rain and wind. I was really fond of the old shelter – it was warm sitting in there in the morning and it gave refuge and comfort for many people in the neighbourhood. People who were cold walking to school, people who might not have a place to stay that night, people who needed a comfortable spot to rest. When it was replaced we thought it was good to be more modern, but now looking at it I know the new one was made so people don’t linger there. It’s now a stop / go space and serves a much smaller number of people. I’ve started noticing changes like this more and more in my neighbourhood.

Portrait of Sione Faletau. Photograph by Sam Hartnett.

Sione Faletau, Kupesi Peau Ongo, 2021, installed in Toro Whakaara at CoCA Toi Moroki. Photograph by John Collie.

Sione Faletau, Kupesi Peau Ongo, 2021, installed in Toro Whakaara at CoCA Toi Moroki. Photograph by John Collie.

Sione Faletau, Kupesi Peau Ongo, 2021, installed in Toro Whakaara at CoCA Toi Moroki. Photograph by John Collie.