-

Author

Heather Galbraith -

Date

24 Jun 2021

Essay

Judy Darragh: Mega Gravity, Ultimate Plasticity

Competitive Plastics

Through the shared flank wall at Objectspace, you can sometimes discern the sounds of shrieking adolescents and ‘attack’ music on repeat, as sweaty bodies career through a multi-level maze trying to shoot one another with lasers. Megazone’s laser-tag energies rub up against the typically more serene space of the gallery next door. Judy Darragh’s Competitive Plastics embraces this cultural collision: the chaos, the ricocheting energy, and with no shortage of fluorescent colour accents. A clear alignment is present in the two large works on discarded film billboard skins, Deadlift and Spotter (both 2012), which echo the sci-fi shoot-’em-up imagery of the neighbours. In these large pictorial customisations, Judy Darragh uses irreverent processes of redaction and collage to transform sexed-up promotional images for mainstream sci-fi/fantasy movie production into artworks more dystopian and playfully anarchic than the originals.

Competitive Plastics is an embarrassment of riches; it wilfully presents as ‘too much’. In today’s world, excessive production and consumption frame our lives, and our cognitive processes strain to filter insanely competitive stimuli. Darragh’s exhibition laments cycles of over-extraction and over-production that endanger our global ecosystems, while readily acknowledging our complicity in these cycles. We just keep making and consuming. Though we have read/heard/seen the warnings, still we continue... perhaps at a marginally slower pace in some clutches of society and an amplified pace in others. The paradox of Competitive Plastics is that its ‘stuff’ has been taken out of circulation in one sphere of distribution (homewares, clothing, industrial retail, surplus stores) and inserted into another – one that is arguably more exclusionary, and oriented towards value systems that prize singularity. The attempts of the arts and culture sector to articulate cultural, emotional and aesthetic nuances struggle to be heard in the frenzy of consumerism we live within. The title comes from a now-closed light-industrial unit near Jonathan Smart Gallery in Ōtautahi, which had bright orange letters proclaiming ‘Competitive Plastics’. Its shuttering suggests that neither competition nor plastics are the answer.

Judy Darragh’s curiosity about everyday, overlooked and discarded things – the mix of utilitarian and decorative objects that surround us in our kitchens, wardrobes and sheds, filling opportunity shops and dollar stores – includes their cultural, ecological and socio-political baggage. Discarded objects are re-mixed and re-considered through processes of critical and inquisitive hand- crafting. Works in the studio are often cheek-by-jowl, sometimes discreet, other times intersecting or languishing. They are an unruly yet diffident bunch, and this continues into the exhibition space. It’s rowdy, a bit impolite – crude1 even.

The exhibition is also wilfully analogue, blisteringly low-tech. These man-made (sic) things have been up-ended, stuffed, skewered, twisted, wrapped and stacked. They have been seen, with all their toxicities and complicities. The sentinel LED light boxes in Smoke and Fire are more commonly seen adorning the frontages of kebab shops, but here become torches of warning. Works festoon most surfaces; they sit on the ground, hang from the lighting grid, rest against walls and, in the case of Laser Droop, protrude sideways (as if the beam of the next-door laser guns has assumed physical form and penetrated the wall – with a touch of erectile dysfunction).

Competitive Plastics celebrates and explores making with your hands, analogue making. The exhibition considers the ways these processes shape our brains and implicate our bodies, and what routes for connection and articulation they offer us in the 21st century.

Through the COVID-19 pandemic the ‘return’ to home-based creative making was palpable, as we struggled to balance our dependency on screen-based social connection. Making passed the time. Physical dexterity – honing a skill through repetition, learning through doing, seeing the fruits of your labours, activating ‘play’ – felt rewarding.

But ‘spare time’ in this context was comparative. Existing labour inequities were exposed through the precariousness of zero-hour contracts, the shrinkage of many realms of business during and after periods of lockdown, and with shifts in global trade cycles. Arts workers suffered and systemic inequities grew.

Through this there was hope that the pandemic might be a catalyst for systemic change; that a strengthening of community bonds through shared struggles, and awareness of vulnerability and anxiety, could lead to greater compassion and understanding. Despite individual incidences of kindness and a breaking down of some areas of social reserve, little systemic change has appeared as Aotearoa has opened up again. Inequities seem greater, and precarity amplified. The pandemic has sparked further questioning. How do individuals currently relate to collective experience?

Why do existing art systems continue to feed a culture of competitive individualism? Can this be bypassed, in a way that ensures makers’ agency and the space for self-expression and self-determination?

‘Plasticity’ is an evocative word. Plastic forms dominate the show (and the title), but there are further resonances. Sculpture is a ‘plastic art’ due to materials being moulded and shaped. In physics, plasticity is seen in the ability of a solid material to undergo a permanent shape transformation in response to applied forces; in relation to brain function, neural plasticity pertains to how the nervous system changes its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli.

This interplay between cognition and exploratory making runs through the exhibition. Judy Darragh is intrigued by contemporary French philosopher Catherine Malabou’s discussion of ‘the fold’, which considers how brain function is impacted through repetition, and how creative and critical agency are in play when an action is repeated. Malabou talks of the ‘first fold’ as creative,2 a process of finding a way, attending to the material and aesthetic properties of what we are working with. The second fold she aligns with addiction, with habit. When a repeated action no longer involves exploratory or responsive agency, when muscle memory takes over, what is in play? When do we move into a space of automatic, rather than conscious response?

Similarly, Sara R. Gilbert has chewed over the analogue process of hand-making – specifically the repetition of hand-skills honed and refined over time – and this practice’s centrality to craft as

a field. She discusses the increasing use of ‘craft’ as a verb, to

craft (popularised/promulgated by craft theorist Glenn Adamson), cautioning that by becoming an action instead of a separate field

of making, craft risks being sublimated into other practices, ‘most notably art and design’.3

How are these ideas related to Judy Darragh’s making? Her practice sits in a space of generative disciplinary liminality. For more than

45 years, Darragh has shown dedication to the crafting of forms, objects and materials. Skills are honed but there are also aspects of improvisational or bodged construction. Aesthetic refinement is deeply present within the work, welcoming the impolite, the gaudy, the ‘unsophisticated’ in ways that are remarkably sophisticated. Processes of assemblage take the source material far from its original function, and may appear casual. Darragh’s methods are not particularly fancy; she uses simple tools and techniques to potent affect.

Obsessively repetitive actions abound: the linking of sock packaging hooks in Cloak; the strips of fluorescent tape wound around extension cables in System; and the link construction in Foil. It is through the scale of repetition that new, curious forms emerge. Ideas of habit and addiction are teased out in Smoke 2, 3, and 4, and Sirens (and Sirens 2 and 3). From across the room, Smoke 2, 3 and 4 appear texturally interesting, frothy collages with acrid yellow balls peppering the surface. On closer inspection they reveal that their imagery is drawn from the explicit photographic health warnings placed on cigarette packets. These works are paired with a triptych of jaundiced ‘sirens’ – collages made from books featuring head and glamour shots from Hollywood starlets of yesteryear with their faces painted a sickly yellow. These ‘temptresses’, renowned for being captivating on the silver screen and ‘selling’ fictionalised lives of riches and glamour, frequently had horrific experiences at the hands of the studio system, subjected to abusive employment contracts, unrealistic expectations in term of their physicality, and lacking agency to generate their own narratives.

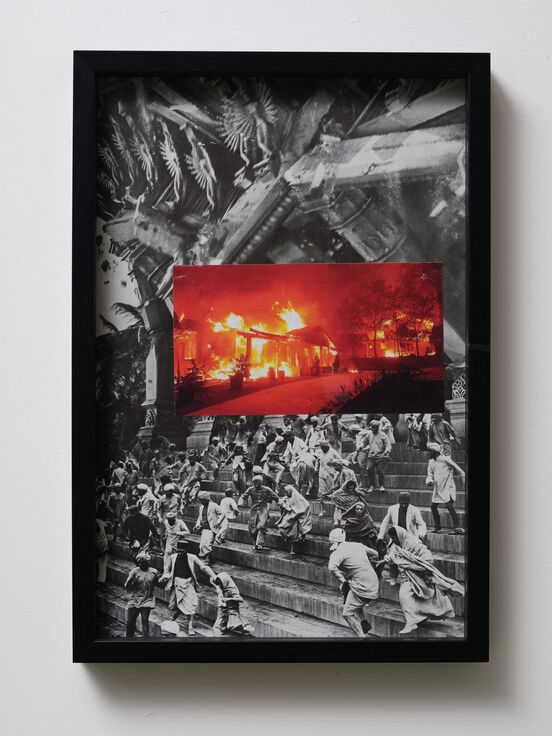

In ...see you in front of the flames, Darragh makes juxtapositions from different screen modes. Imagery from early-to mid-20th century cinematic re-enactments of social gatherings (through war, protest or riot) – both fictional and ‘based on a true story’ – are collaged with internet-sourced images of more recent web-reportage uprisings (e.g. the 1992 LA riots, the 2010-12 Arab Spring uprisings).

Considering how protest and dissent is communicated and imaged is particularly complicated in a time of surveillance culture, deep fakes and social media platforms that no longer maintain a veneer of neutrality.

Bodily references also abound. Stiletto uses ‘bedroom shoes’, their soles showing no evidence of scuffs from concrete or stains from grass. These shoes are stupendously high. They render the wearer precarious; demand serious balance training to dance, walk or run. Their uppers are ‘luxurious’, sensually configured. They change the gait of the wearer, calf muscles protruding, knees bent, bottom jutting out. Here, the shoes themselves are rendered immobile, forming a symmetrical negative space, yonic in character. But it would be reductive to essentialise these shoes in relation to heteronormative gender, given you are as likely to see these shoes being employed on a ballroom runway, or by pole dancers of all genders, as you might within a cisgendered porn boudoir scene. Stiletto references improbable sexual positions... knees akimbo! Does the work symbolise self-determined pleasure, or unwanted restriction, or something else entirely? Stiletto interrogates complex object resonances in a time when our options for self-determination are expanding. Yet this is also a time where we know that violence experienced by women (with an even higher per capita rate affecting trans women) is accelerating, with devastating consequences.

The symmetry in Stiletto chimes with other works, including Code, an unfurling jewel-coloured ink scroll, in which stacked and overlapping symmetrical forms in translucent coloured inks echo the monochrome ink blots of Rorschach tests, a form of psychological testing developed in the early 20th century,4 popular in the 1960s and 1970s, and subsequently derided by many as pseudoscience. Pattern recognition and interpretation were used to diagnose conditions of psychological or cognitive difference. The potential for subjective results was considerable, and despite different testing and evaluation systems evolving, the test’s efficacy as a diagnostic tool remains contested.

Choir lines up standing forms of symmetrical stacks: a series of mouthpieces or speaker cones, fashioned from vessels, moulds, buttons, blocks and balls. Regimented in their posture, these objects of containment, culinary utility and play have been transformed into entities that riff off all manner of bodily orifices and appendages. Pelvic gives a clear steer in terms of its figurative referencing. Collected vintage and new sheep skin, possum fur and other pelts form a central core image hard to miss, particularly with the tufting red tendrils that radiate from either side of the central slit. It takes the metaphor of the fold to a considerably more labial place.

In Para, a cluster of rolled, bound, standing foam columns hint

at some form of gathering (in solidarity?). The title nods to the prefix para-, meaning beside or adjacent to (as in paramilitary), or indicating something that protects or wards off (as in parachute). It’s also a

nod to the Para Rubber foam rubber 5 franchise in Aotearoa. Para's rolls of different heights, weights and colour are all bound, cinched

in at various points to improve their structural integrity. Even in their rainbow toxicity, the gathering feels somehow reassuring – a foam whānau sticking close to one another.

Mono incorporates and plays with a ubiquitous design form: the lightweight, stackable Monobloc chair. A mass consumer product, its affordability suggests democratic access, yet its production method/ materiality (moulded petrochemical plastic) is not ecologically sustainable. There have been many iterations of mass-produced chairs since the 1920s. The Monobloc was originally developed in 1946 by Canadian designer D.C. Simpson. Variants and knock offs abound (though snazzy high-end versions have also been produced), and millions of the chairs have been produced globally. So familiar is the Monobloc in our landscape, it has been held as an example of a ‘context-free’ object.6 Darragh’s gathering of other common- and-garden objects, combines the chairs with funnels, holes, nested things, and balanced combinations, to establish relationships of co-dependency, to see if things fit together and to explore how complementarity and flow can be manifest in sculptural form.

The relating of neuroscientific research to fields of living (including creative practice) is hot right now. We are desperately hoping to gain a deeper understanding of the brain-body nexus. Brain function imaging (through functional near-infrared spectroscopy or magnetic resonance imaging) has dramatically improved, but there is still much to know. The health benefits of creative practice are receiving increased attention and evidence for them is regularly incorporated into advocacy documents arguing for a more central and substantive valuing of the benefits of creative expression.

As the world’s population ages, higher rates of the population affected by dementia are predicted.7 Research is examining how a better understanding of neuroplasticity might assist in maintaining proficiency or slowing effects of dementia. There are many studies of what goes on in the brain when we make or engage with art, and how individual self-expression may help with both cognitive processing and perceptions of wellness.8 Neuroplasticity stimulated through repeating tasks of relative complexity to aid the recovery of stroke sufferers is also of current interest.9

Judy Darragh cites as influential an image her son Buster shared with her that had been doing the rounds on the internet of an AI rendering of the visual perception commonly experienced by stroke survivors.

People who have had a severe stroke can often make out shapes and colours but not fully comprehend what objects are or their relationship to each other.

Similar feelings of partial familiarity, indeterminacy or abstraction are common within the language of visual art. In Darragh’s work Stroke (2021), she has attempted to simulate – manually – the type

of image that an AI algorithm might generate from collated data. This rather meta work sits alongside Crunch (2021), which provides a forensic view of composite rubber chip foam with a striking resemblance to cellular forms or geological close-ups.

What continued research will tell us into how our bodies and brains interact is a subject of much conjecture and imagination. In the meantime, Judy Darragh continues to be curious about our material world and strives to navigate through the toxicities and contradictions with optimism and determination, and a belief that art and creative expression remain central to human existence.

Judy Darragh ONZM (b. 1957, Ōtautahi) is renowned for her sculptural assemblages, collage, video, photography and poster art. During

the 1980s, Darragh’s trademark, eclectic iconoclasm modelled a critical position in response to rampant materialism and free-market reforms. In 2004 Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand mounted the survey and catalogue Judy Darragh: So... you made it? Darragh was central to the development of ARTSPACE Aotearoa and the artist-run spaces Teststrip and Cuckoo. She has been an educator and mentor to many artists. Co-editor of Femisphere, a publication supporting women’s art practices, Darragh continues to exhibit throughout Aotearoa, and her works are held in major public collections. She lives in Tāmaki Makaurau.

Heather Galbraith (b. 1970, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a curator, writer and educator. Initially an artist, Galbraith undertook an MA in Curating

at Goldsmiths’ College. She was Exhibitions Organiser at Camden Arts Centre, London, for seven years, then held senior roles at City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi; the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa; and Whiti o Rehua School of Art, Massey University, where she is now Professor of Fine Arts. Galbraith has had a long association with New Zealand at the Venice Biennale, and was Managing Curator SCAPE Public Art, Ōtautahi, from 2016 to 2018. At Westlake Girls High School, Galbraith had an inspirational sixth-form art teacher: Judy Darragh.

1. Artist Louise Menzies used this term looking at the works in Judy Darragh’s studio in the run-up to this project, much to Darragh’s delight.

2. Catherine Malabou, ‘The relation between habit and fold’,

European Graduate School Video Lectures: Public open lecture

for the students of the Division of Philosophy, Art & Critical

Thought, European Graduate School, Saas-Fee, Switzerland, 12 August 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=EglV1eVTrpU (accessed 30 April 2021).

3. Sara R. Gilbert, ‘A Widening Chromaticism: Learning Perception in the Collective Craftwork of the Encounter’, in Material Perceptions, Documents of Contemporary Crafts No. 5, edited by Knut Astrup Bull and André Gali, Norwegian Crafts, Oslo / Arnoldsche Art Publishers, Stuttgart, 2018, p. 51.

4. Developed by Swiss psychologist Herman Rorschach in 1921. There were precursors to Rorschach’s test and related book Psychodiagnostik, including the use of inkblots by German doctor Justinus Kerner, and French psychologist Alfred Binet.

5. Foam rubber, originally made from natural latex and used in Mayan and Aztec cultures as early as 500 BC, was developed in the 1900s with synthetic variants, and today’s polyurethane versions are used within construction, furniture and transportation. Processes for utilising production waste and recycling product are growing, but remain minimal in terms of any real circularity of use.

6. Ethan Zuckerman, ‘Those White Plastic Chairs – The Monobloc and the Context-Free Object’, quoted in Claude, ‘Monobloc

Chairs – Controversial Symbol Of Capitalism Or Outdoor Decor?’, ChairPickr, https://chairpickr.com/all-about-monobloc-chairs/

(accessed 2 May 2021). There have been many variants of the 9. Monobloc since 1946, inspired by Simpson’s design and by the Chair Universal 4867, designed by Joe Colombo in 1965. The child-scaled versions in Darragh’s work seem more related to Fauteuil 300 by Henry Massonnet, designed in 1972, or Garden Chair by the Grosfillex Group, designed in 1983.

7. World Health Organization, ‘Dementia’ fact sheet, 21 September 2020, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed 30 April 2021).

8. Girija Kaimal, Hasan Ayaz, Joanna Herres, Rebekka Dieterich- Hartwell, Bindal Makwana, Donna H. Kaiser and Jennifer A. Nasser, ‘Functional near-infrared spectroscopy assessment

of reward perception based on visual self-expression: Coloring, doodling, and free drawing’, The Arts in Psychotherapy, vol. 55, 2017, pp. 85–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.05.004 (accessed 30 April 2021). In other studies, such as MinDArT in Wellington (www.medartdrawing.com), material and digital drawing exercises have been used to test whether drawing can help maintain fine motor skills and to improve communication, wellbeing and self-esteem in people with dementia and their supporters.

9. James R. Carey, Ela Bhatt and Ashima Nagpal, ‘Neuroplasticity Promoted by Task Complexity’, Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, January 2005, vol. 33, issue 1, pp. 24–31, https:// journals.lww.com/acsm-essr/Fulltext/2005/01000/ Neuroplasticity_Promoted_by_Task_Complexity.5.aspx (accessed 30 April 2021).

Judy Darragh, Lunge (detail), 2021. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

Judy Darragh, Foil Chain, 2021. Photographer: Samuel Hartnett.

Judy Darragh, Lunge (left) and Laser Droop (right), 2021. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

Judy Darragh, Capital, 2021. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

Judy Darragh, ...see you in front of the flames, 2020. Photographer: Samuel Hartnett.

Judy Darragh, Pelvic, 2021. Photographer: Samuel Hartnett.