-

Author

Emma Ng -

Date

19 May 2019

Essay

The Room: The Edit

Emma Ng

‘It is in the living room shielded by sofa cushions and huddled behind a ranked army of bric-a-brac that the individual searches for a safe haven from the shock of modern urban life. It is in the phantasmagoria of the interior that objects appear deprived of their immediate usefulness and acquire new meanings and functions, as they are cast in a system of personal associations and elective affinities. What talismans shroud our dwelling places.’ – Massimiliano Gioni, The Keeper, 2016

Presenting an intermediary point between public and private, the domestic interior operates both as an inward-looking source of refuge and relief in an increasingly busy and complex world; and as a visual display of self-expression – a construction of how we imagine ourselves being seen.

The appearance of the contemporary interior is everywhere. Emanating far beyond the pages of the glossy magazine spread, stylised impressions of domesticated spaces appear to us in Instagram and Pinterest feeds, real estate listings and renovation reality TV. Staged living-room settings can be found in hotel lobbies, shared offices and in the voluminous corridors of the suburban shopping mall, signifying opportunities for relaxation and sanctuary. Thus visualised in arrangements of objects and in choices of decoration and design, the interior chronicles the human experience of dwelling through material culture. It communicates social codes for behaviour that reflect the key values of its occupants in relationship to survival, utility, comfort and privilege.

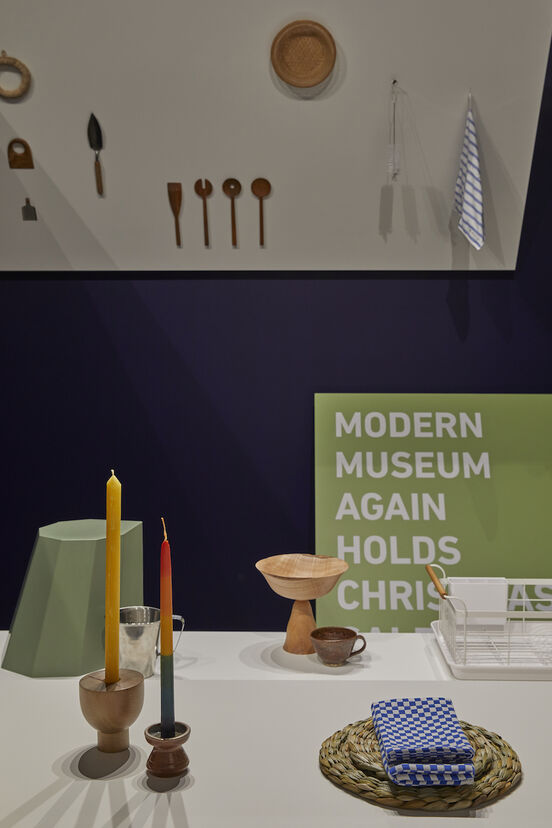

The Room examines how human experiences of interior spaces are constructed and expressed through ornamentation and design. This large-scale exhibition presents four curated environments. Conceived as rooms, each explores the social and cultural dimensions of domesticated spaces. Together, they share a focus on the methods by which interior architecture communicates manifold languages of identity and self-expression.

Within a series of interconnected built structures designed by Knight Associates, curator Justine Olsen and jeweller Karl Fritsch, design writer Emma Ng, curator Ane Tonga and artist Ani O’Neill, and interior designer Rufus Knight with architect Mijntje Lepoutre each present an interior scene for The Room.

Existing somewhere between living room, stage set, and design-fair-display, The Room casts the interior as a constructed display system; a set of configurable props and spatial treatments that, when redrawn, brings into close view our cultural and political associations with the objects and architecture of lived spaces.

— Kim Paton: Director, Objectspace

The Edit Trivets, clothes pegs and colanders are unlikely objects for exhibition. It’s especially odd to see them in a gallery when the same items are displayed in a shop just down the street. But the reality is that life pays no attention to such distinctions. Instead, there’s a constant play between these two types of spaces – they’re often shaped by the same cultural tastes and they likely even share an overlapping set of patrons.

Rather than pretending to an arch separation of commerce and the gallery space, The Edit explicitly collapses these contexts into one another, positioning our behaviours in these spaces as inevitably related. New York’s Museum of Modern Art has a long history of exhibiting domestic items. In its first few decades, many of its design shows were paeans to a spirit of hopeful modernity. In particular, a series of exhibitions that began with 1938’s Useful Household Objects Under $5.00 is referenced here.1 Like that series, this show presents a glimpse of the everyday aspirations of the moment. The price point is roughly analogous too: US$5 then is about NZ$130 today.

In bringing together the display languages of galleries and retail, The Edit considers their mutual forms. Within both domains hums the drive to curate and catalogue, the curator and retailer both employing strategies of selection and storytelling. ‘The museum and the department store are two sides of the same coin,’ writes Mary Anne Staniszewski in her history of MoMA’s exhibition installations, characterising both as ‘institutions of modernity and modern capitalism’ born of the nineteenth century.2 Indeed, we might trace their emerging twinship to industrial displays like the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851.

In the twentieth century, we largely consumed interiors through glossy magazine photographs. The architecture historian Beatriz Colomina has suggested that architecture became modern by engaging with mass media. Circulating imagery became the site of architectural consumption – a new intersection between privacy and publicity. Today, those glossy moments bombard us from all angles. We encounter the idea of the interior constantly, as an amorphous cloud of images shared and re-shared through online stores and Instagram feeds, and even Airbnb listings or Netflix shows. At Objectspace, The Edit is poised somewhere between online and offline, borrowing display strategies from each.

The retailers that these objects are drawn from are very particular kinds of shops, because The Edit looks at a very particular strand of contemporary life. It straddles the everyday and the aspirational, searching for the idea of the interior – the moments of story and promise that make retail so compelling.

A particular kind of minimalism is currently ascendant, propagated by figures like American duo The Minimalists and the Japanese decluttering specialist Marie Kondo. Their approaches are often framed as a philosophical endeavour – while they work in sympathy with narratives of mindful consumption and environmental sustainability, encouraging people to live ‘meaningful lives’ is their ultimate goal. They tout healthier relationships, career success and even weight loss as outcomes of their processes.

Kondo, in particular, encourages us to own less by believing that the things that we do have mean more. Really, hers is an enduring philosophy skinned for the present moment – a search for greater meaning and authenticity parsed through the objects that populate our everyday lives. William Morris, in the 1880s, suggested that ‘If you want a golden rule that will fit everything, this is it: Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.’ Marie Kondo asks us to ‘take each item in one’s hand and ask: “Does this spark joy?” If it does, keep it. If not, dispose of it.’ Discarded objects, she encourages us, should be thanked for their service before being discharged. It may not be surprising to learn that Kondo spent five years as an attendant at a Shinto shrine.

The objects selected for this display are sold with their own stories: they’re handmade locally, sourced from anonymous craftspeople in Japan, or are international design canon classics. We can read into them as a taxonomy of contemporary tastes – for example, we must wonder at the continual exotic appeal of Japanese craft. But it is the use of the story, rather than the story itself, that really interests me here. If the Useful Household Objects series celebrated a hopeful modernity, we must read these stories of handcrafted provenance against the grain of contemporary life.

The blurb for Beatriz Colomina’s 1996 book, Privacy and Publicity, suggests that the domestic interior ‘constructs the modern subject it appears merely to house’. The Edit builds on this connection between the domestic interior and psychological interiority – musing on the potential of these objects to reveal an idea of the interior that points to a grander contemporary desire, in the sense of Jacques Lacan’s objet petit a.

Lacan suggested that this desire can be perceived only when looked at obliquely. At MoMA in the late 1930s – the ‘laboratory years’ for their design shows – the Bauhaus artist and designer Herbert Bayer began exploring display strategies that embraced our expansive field of vision. He hung chairs from walls and presented information on angled panels to match the sweep of the human eye. Bayer’s motivations were physiological rather than psychological, but there is something to be said for looking at the familiar from an unfamiliar angle.

Home remains a last frontier – the final domain of control – for many people. Together the objects in The Edit represent the fantasy of a home that crackles with sparks of joy. Right off the shelf, they’re storied objects worthy of Marie Kondo’s animist regard. They respond to our taste for things that we feel mean more – appealing to us as we search for meaning and authenticity in the detail of everyday life. — Emma Ng

1 Conceived as touring exhibitions, the series sought to show that well-designed household goods could be purchased at affordable prices. It continued annually for nine years after the first exhibition in 1938, though the price point changed. The final exhibition featured products under $100.

2 Mary Anne Staniszewski, The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1998, p. 174.

Emma Ng, The Edit for The Room, 2019, Objectspace. Image: Samuel Hartnett.

Emma Ng, The Edit for The Room, 2019, Objectspace. Image: Samuel Hartnett.