-

Author

Lucy Treep -

Date

18 Dec 2018

Essay

The Single Object

The Chaise Longue and the Library

Walking through the doors of the Architecture and Planning Library at the University of Auckland is like entering a cabinet of curiosities, or a wunderkammer, a ‘wonder-room’. The library is an airy space where a large collection of books mingles with a treasure-trove of objects: measured drawings; photographs of buildings, stone, wood, plaster and cardboard models; great New Zealand art; student artwork in frames designed by lecturers; and pieces of historic and designer furniture. Through the permanent display of these objects, the volumes on the shelves are placed in a context that speaks clearly of the lively history and productivity of the School of Architecture and Planning, and provides tangible evidence of its cultural wealth.

In 2018, the University of Auckland announced plans to close the library (along with the Fine Arts Library, the Music and Dance Library, and the Tamaki and Epsom Libraries). The collection of books will be split: some of it will be absorbed into the general collection at the main university library, some will be stored at the Tamaki site, and some will be destroyed due to lack of space. The university promises it won’t burn the ‘spare’ books as it did when it recently closed the Engineering Library – it will simply shred them.

But what will happen to the collection of objects when the books are gone? The conversation between the books and the objects will have been severed. One item that seems to have jumped straight from the pages of what was once one of the most eagerly read series of volumes in the library is the elegant chaise longue that sits just inside the entrance.

The chaise, familiar to decades of student library users and as much an artwork as a piece of furniture, is a numbered reproduction of the iconic 1928 ‘chaise longue basculante’ (tilting chaise longue), designed by Swiss/French architect Le Corbusier in collaboration with his cousin and architectural partner, Pierre Jeanneret, and employee Charlotte Perriand.

New Zealand architect Sir Miles Warren, who was a student at the School from 1949-51, recalled the thrill of the arrival of books by Le Corbusier in the Architecture Library in his autobiography: “The first three of his eight-volume Oeuvre Complete arrived at the school one after another and quickly became our generation’s bible, each plan and illustration eagerly devoured and committed to memory”.

Volume II of Oeuvre Complete contains a description of the chaise longue and a photograph of it with Charlotte Perriand relaxed along its length, demonstrating its virtues. In 1927, having successfully graduated from design school but uncertain what to do next, Perriand happened to read two books by Le Corbusier: Vers une architecture and L’art décoratif d’aujourd’hui.

“[T]he wall rolled open! Or rather it burst apart… What could I do? I wanted to work for Le Corbusier. And so I paid him a visit,” she says in her interview for Pascal Renous’s, Portraits de decorateurs.

Le Corbusier initially dismissed her, rudely saying he didn’t need a ‘cushion designer’, but on visiting her graduate display at the Paris Salon d’Automne, he hired her on the spot. Although, Perriand was technically employed by Le Corbusier, she was not paid for her work – to pay her way she resourcefully maintained a successful private interior and furniture design practice. This didn’t seem to dampen her enthusiasm; photographs of the atelier show her with a large smile in a group of unsmiling men.

Le Corbusier had just been to an international display of modernist architecture at the Weissenhof in Stuttgart, where he’d been inspired by cantilevered tubular steel furniture designed by Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe and Mart Stam. He immediately sought a design specialist who would take his loose sketches of furniture and formulate a response in steel and tubular steel, ensuring he didn’t fall behind in this field. Ideas of solidity based on expressions of mass were out. Cantilevers, lightness of material, and solids floating on voids expressed Le Corbusier’s architectural vision of a new way to live.

Perriand credits Le Corbusier with setting the design parameters and for suggesting the basic form of the furniture. She and Jeanneret worked out the designs and details. She took it upon herself to assemble prototypes and searched hardware stores for materials, and furriers for the pony and calf skins. She then invited Le Corbusier and Jeanneret to her apartment where she surprised them with the finished pieces arranged in the appropriately domestic setting.

The Chaise Longue in situ at The Architecture and Planning Library. (Image: Samuel Hartnett)

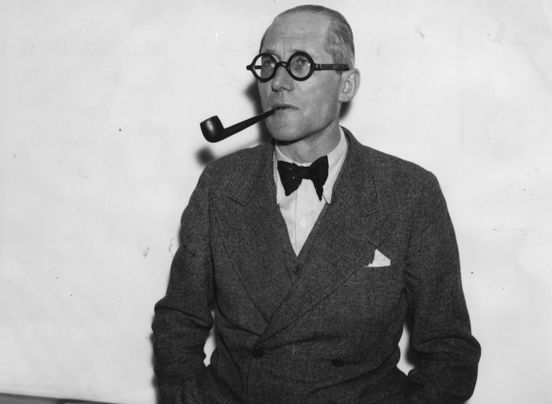

Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier (photo by Hudson/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The Architecture and Planning Library at The University of Auckland (Image: Samuel Hartnett).

Le Corbusier was amused by her initiative and delighted with how stylish the pieces were, and in 1932 he credited her for having the sole responsibility for the execution of all ‘our domestic equipment’. As he later discussed in Oeuvre Complete, Le Corbusier was particularly pleased with the way the chaise was able to adopt any position, always balanced on its own without mechanical intervention.

Perriand set up a promotional photograph of the chaise longue with her reclining on it with her head tilted away from the camera, and her legs higher than her head. Though demure by today’s standards, the image is amazingly electric, and demonstrates clearly the closeness of the design to the shape of the human body. The image is reproduced in miniature in Oeuvre Complete along with another in which the bottom section of the chaise supports Perriand’s legs in a lower position.

Despite Perriand’s role, in 1983, the Architecture and Planning Library was offered its very own “Le Corbusier chaise longue”. In the 1980s Perriand’s significant contribution to the design and production of the Le Corbusier/Jeanneret furniture was relatively unknown, and Pierre Jeanneret was also a lesser name. Having a ‘Corb’ was the thing.

That year, the architecture students hosted the biennial Oceania Congress of Architectural Students with an event commonly known as the ‘Gone to Kiwi’ conference (named in reference to the pub across the road where students and staff regularly gathered). Over five days in mid-term break, Gone to Kiwi welcomed 450 staff and students from 19 architecture schools around Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea. Key speakers included American hippie-visionary Paolo Soleri, Australian architect John Andrews, Auckland alumni Peter Beaven who flew in from London, poet Sam Hunt, and local activist Tim Shadbolt. Famed French mime Marcel Marceau, somehow procured by student Dorita Hannah, appeared at the opening – and spoke!

From the beginning of the year the Architecture and Planning Library staff were involved with student organisers in obtaining information on architects worldwide, to whom the students then wrote. In a spirit of lighthearted openness the library set up a display of replies from the national and international names, creating, as librarian Wendy Garvey noted in the library’s 1983 annual report, “a great deal of interest and amusement”.

Gone to Kiwi was so successful it made a profit, and student organisers approached dean Alan Wild for suggestions regarding the unexpected funds. Following his advice, the money was used to gift the Architecture Library two numbered Cassina reproductions of architectural furniture: the ‘Hill House, 1’ ladder chair by Charles Rennie MacKintosh and the ‘LC4’ chaise longue by Le Corbusier, Jeanneret and Perriand. Both are still in the library.

There is a history of gifting associated with the library. Its founding collection relied largely on donated works, and the Gone to Kiwi donation can be seen as part of a thread of generosity and reciprocity that binds the Library to its community.

Though the model is an instantly recognisable classic of furniture design and exhibited in galleries around the world, it was decided that, what Le Corbusier called the ‘beautiful resting machine’ should be experienced in the library through personal use as well as by viewing. For 35 years the chaise longue has been the place to be for those wanting to look through one of the publications on the new-to-the-library shelves, or for those simply wanting to relax in style. It now shows obvious signs of wear but is still perfectly comfortable and a thing of beauty: a perfect balance of form and function. Wendy Garvey, Architectural Librarian from 1976-2015, says that having watched generations of library users lie on it, read on it and even sleep on it, she is convinced it is the perfect chair in which to enjoy a book.

At Garvey’s retirement party, I was amused to see what looked like a large refrigerator, still in its box, wheeled in. As she gave her elegant farewell speech, she patted the box, and said she didn’t need to open it – she knew what was in it. Wendy was delighted to receive her own LC4 chaise longue, which is now out of the box and in a place with good reading light. She says it invites you in, like all good design does.

Whether that first LC4 will continue to embrace readers is uncertain. Along with all the other treasures that presently make the library what it is, the future of the chaise longue is unknown. Sue Roberts, the university librarian, says formal discussions about the objects in the library have yet to be held.

The original Gone to Kiwi student committee are very interested in the fate of the chaise. They are concerned that outside of the library there may not be a place where it would be safe but still available for use. As the 1983 student congress was in part a work of collaboration between the Wellington School of Architecture, and the Auckland School, some have suggested that, in a celebration of that collegiality, the chaise should now be gifted to the University of Victoria, Wellington, School of Architecture Library.

This continuation of a tradition associated with the library might mitigate the sense of loss associated with the displacement of the chaise. Sadly, there seems no mitigation of the proposed loss of the library.

The Architecture and Planning Library at The University of Auckland (Image: Samuel Hartnett).