-

Author

Sebastian Clarke -

Date

30 Nov 2021

Essay

The Single Object: Flamingos in stitches

Sebastian Clarke recounts the making of a new embroidered curtain for Auckland’s Civic theatre – the local story of a truly global fabric.

October 28 was all set to be the opening of the Auckland leg of the New Zealand International Film Festival. For Auckland’s film enthusiasts, the festival’s opening night is a beloved affair: assembling beneath the ersatz, starry sky of The Civic theatre and looking ahead towards three majestic flamingos wading against a velvet backdrop. The embroidered flamingo curtain has served as the most celebrated support act before any concert, movie screening, or stage production for generations of Civic visitors. Yet, like so much of our local design history, the story of The Civic’s flamingo curtain is not well-known. In fact, two almost-identical flamingo curtains have hung in The Civic. Unpacking the history of both curtains tells a story about Auckland’s most treasured theatre and the eight local women who embroidered it.

If you’ve ever wanted a crash course on the modern global history of going to the movies, there is nowhere better in New Zealand to visit than Auckland’s Civic theatre. Constructed in 1929, the theatre was built during the golden age of Hollywood when the popularity of moviemaking (and movie-watching) was skyrocketing. Growing audiences required bigger cinemas, and cinemas didn’t just expand – they started to look dramatically different too. The “atmospheric theatre” arrived in the 1920s, a new style for fitting out theatres that aimed to provide an immersive, engaging experience for patrons. Going to the movies has always been a form of escapism, and atmospheric theatres were designed to heighten that feeling. Interior decoration, architectural detail and coloured light projections were all employed excessively to give visitors the sense of being transported to the faraway and glamorous locations they could see on screen. The atmospheric style was most popular in North America, where theatre interiors regularly borrowed the design languages of Italian Renaissance and Spanish Revival architecture.

Atmospheric theatres were less common elsewhere, and Auckland’s Civic theatre is the largest remaining example in all of Australasia. It is also possibly the only to draw inspiration from Indo-Islamic architecture, incorporating elaborate Mughal designs (like minaret towers reminiscent of the Taj Mahal), and hundreds of glistening gold big cats, Buddhas and elephants. Two Swiss men, architect Charles Bohringer and artist Arnold Zimmerman, were behind the theatre’s design. While there aren’t any known records crediting them with the design of the flamingo curtains, it is very likely they were responsible for the towering birds on the mainstage. The design of the curtain was unusual – a single piece of fabric that lifted to the top of the stage rather than two separate pieces that could be pulled to either side. Its elegant avian scene was realised in total Art Nouveau style – ginormous, curvy flamingos standing either side of a central flowing river, flanked by leafy bushes underfoot and blossom branches overhead.

As the years went by, the flamingos remained on The Civic’s stage, mute winged witnesses to the events unfolding before them. They were there for the early boom and bust of theatregoing that occurred during the Great Depression. Later, during World War II, they would have seen the Wintergarden nightclub within The Civic host racy cabaret performances where dancers like Freda Stark gained icon status. Over time, the flamingos would have also noticed the incremental deterioration of the theatre – cobwebs built up, plaster started to fall from the ceiling, ornaments went missing and leaks developed. The decline in the theatre’s condition reflected its perilous financial position – the economics of running an almost 3,000-person capacity theatre were not easy.

In the late 1960s a decision was made to convert the Wintergarden into a theatre, allowing it to be used for smaller, more cost-effective movie screenings. Unfortunately, it was determined that The Civic’s grand Wurlitzer Organ would need to be moved as part of this redevelopment. The organ was offered for sale, and eventually purchased by classic car collector Sir Len Southward, who restored and installed it in a purpose-built theatre on Wellington’s Kapiti Coast. As part of the exchange, Southward also secured The Civic’s signature curtain which was hung alongside the Wurlitzer Organ in its new home. The flamingos had officially flown their Auckland nest.

Meanwhile, the state of The Civic continued to deteriorate, and talks of demolition grew loud. Supporters of the theatre realised what was at stake and advocacy for protecting The Civic gained momentum. The Historic Places Trust (now Heritage New Zealand) listed the building for its heritage value in 1985, and in 1988 filmmaker Peter Wells directed The Mighty Civic, a stirring, exuberant tour through the theatre which drove public support for its protection. This advocacy had a big impact when, in the late 1990s, the Auckland City Council (which had recently become the owner of the theatre) commenced a landmark restoration of the entire complex.

On election weekend in 1999, while Helen Clark was on her way to winning her first term as prime minister, Auckland City Council heritage adviser George Farrant was preoccupied with a victory of his own. He was in Paraparaumu on the Kapiti Coast, and had finally been reconnected with a very important textile. Farrant had the responsibility of overseeing the monumental restoration of The Civic and had determined that within the almost $42 million budget there would be sufficient funding to produce a new curtain for the theatre. Reinstating the original curtain was not an option. From its time hanging out on centre stage, the curtain had deteriorated significantly – its fragile fibre now showed the effects of close to 50 years displayed in front of cigarette-smoking theatregoers. The new curtain was to be a near-perfect replica of the original. Farrant diligently created a grid with string, documenting each precise detail of the huge 18m wide curtain in hundreds of 20cm squares.

Farrant needed the right people to transform those hundreds of squares back into curtain form. The guild of embroiderers in New Zealand were approached first. They had more than proven their capability when, in 1991, over 400 local embroiderers completed four embroidered wall hangings for Shakespeare’s Globe in London. Word about The Civic’s curtain project found its way to Robyn Tubb, from North Shore sewing group the Stitch Connection; she was immediately interested. But before committing, she and her group had to see the original, close-up, to understand what they were signing up for. A segment of the original travelled up to Auckland for inspection. Its dust, smoke and age left the Stitch Connection members coughing, but they departed the meeting filled with excitement for the enormous project.

The logistics of the project were immense. After an eight-week journey from the Netherlands to Auckland, the velvet for the curtain arrived already stitched together; it immediately had to be unpicked into six large pieces to make it manageable to work with. But the huge amount of fabric still required an equally large studio for the women to work from.

They found a warehouse for rent in Albany with a mezzanine layout. Scaffolding was specially made for the space, so that the curtain could be extended and worked on in big sections. Another complexity involved in recreating a 1920s embroidered textile almost 80 years later was the need to remain faithful to the technologies of that time. The group quickly realised they would need a ‘Cornely’. Most likely to be found in museums these days, a Cornely is an embroidery machine first developed in 19th century Paris to mechanise the kinds of stitches that would otherwise have to be completed by hand.

The council put out a call-out in its weekly circular City Scene (remember that beacon of local government communications?) and as luck would have it, two Cornely owners came forward and one of the machines proved up to the challenge. Using a Cornely required a team effort: one person in front of the machine, their hands and somehow also their knees involved in the process of moving fabric under the machine’s needle, and another guiding the shape of the embroidery, ensuring the fabric didn’t spill over the scaffolding too quickly. The machine required regular repairs from being used so intensively.

July 2000 was a month of intense activity for the Stitch Connection. They had to complete all of the appliqué, hand stitching and airbrushing of the fabric before August, all while still working their day jobs – with the exception of Jo Turner who took the month off and “Cornely-ed her life away”. Weekends saw the full team working, often from 7.45am, and a roster of helpers were called on for support during the weekdays. The appliqué allowed the women some of their own creative input into the project, selecting suitable colours and fabrics for the hundreds of leaves found across the curtain. With such an ambitious and demanding project, it would be easy to focus on all of the challenges and difficulties the group encountered, but like any stitch group project, there was also a great deal of fun, laughter and camaraderie.

Once the stitching was completed, George Farrant airbrushed the curtain to give it the muted quality of the original. Rhinestones from Japan were added as finishing touches. The women met their project deadline and the completed curtain was delivered to The Civic in early August, a week before the theatre’s official re-opening.

Since 2000, The Civic has been the Auckland home of the New Zealand International Film Festival, where old and new audiences are charmed by the flamingos each year. When the festival rolls into Auckland, the members of the Stitch Connection can be found in the audience at The Civic, admiring their feat of artistry.

The original curtain remained hanging in Southward Car Museum’s theatre until 2019. After a century-long and eventful life, the curtain was in a very poor state and the large, heavy fabric had become a fire hazard in the museum. The decision was made to dispose of the flamingos. Robyn Tubb, one of the women who worked on the replica curtain, was sanguine. “They have a life,” she said of all textiles, “and it does end.”

The making of the flamingo curtain reveals a truly international stitching together of ideas about design. The curtain was created for a theatre that took style inspiration directly from North American interior trends. Then, The Civic’s Swiss-born architects chose Indian patterns, symbols and design references, including the flamingos wading among water lotuses. And again, the construction of the new curtain in 2000 shows how even the material and equipment were similarly global, with Dutch velvet and French embroidery machines key to the project. Yet, the final act in re-creating the curtain was completed by a group of local women who were supported by a raft of community helpers. They constructed a curtain that is now imprinted in the collective memory of all who have taken in the beauty of The Civic theatre, a memory so full of excitement – the joy of social gatherings and celebration of creative spirit.

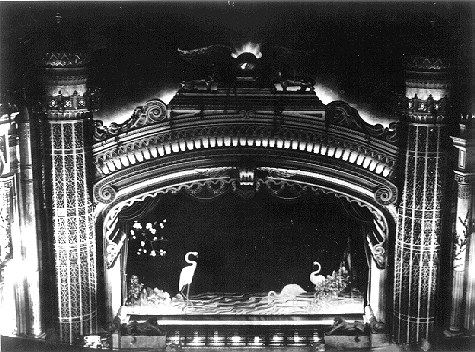

The original Civic curtain. Photo: collection of Judy Clearwater and Robyn Tubb.

The Wurlitzer Organ in the Civic, with the flamingo curtain visible in the background. Photo: public domain.

The new curtain being hung. Photo: collection of Judy Clearwater and Robyn Tubb.

The Civic curtain. Photo: collection of Judy Clearwater and Robyn Tubb.

The Stitch Connection: Susan Brookes, Judy Clearwater, Robyn Duffy, Prue Georgeson, Andrea Old, Jan Rhodes, Robyn Tubb, Jo Turner, with Auckland Council heritage staff George Farrant and colleague. Photo: collection of Judy Clearwater and Robyn Tubb.

Jan and Jo working away. Photo: collection of Judy Clearwater and Robyn Tubb.

The curtain comes together. Photo: collection of Judy Clearwater and Robyn Tubb.

The late Bill Gosden in front of the curtain. Photo: courtesy New Zealand International Film Festival.

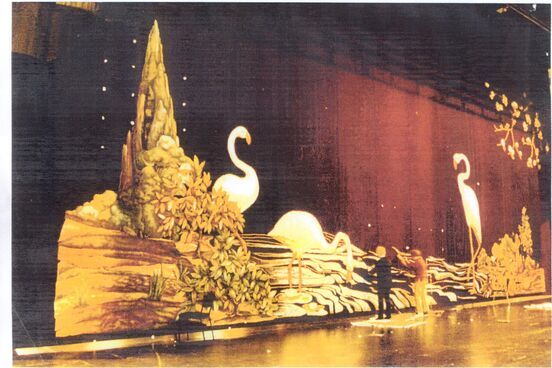

The enormity of the flamingos. Photo: collection of Judy Clearwater and Robyn Tubb.