-

Author

Icao Tiseli -

Date

4 Jan 2022

Essay

Toro Whakaara: Edith Amituanai

My daughter was quite young and drew an awesome design - a high schooler saw it and wanted it for their cultural group. She answered and said, ‘No.’ Being that young and so aware of the worth of her work. The adults caught wind of this and were disappointed by her and asked her why? They tried to pressure her, but still she said no. She eventually replied, ‘You could never. I’ve got designs forever.’ I was so proud of her.

– Edith Amituanai

Onehunga, Ōtara, Rānui: what do these spaces have in common? Rich cultural communities. This is not a lens but a reality, an honest calling that Edith hears and answers with each click of her camera. Edith proudly works and represents her community in the fierce but vibrant space of Rānui. Hearing Edith talk about her work, one can make out the footsteps of her walks around the fabric of her community, mapping that inherent understanding of her place.

As the ‘Rānui flâneur’, a title coined lovingly to convey the earned relationship she has made with Rānui, Edith observes how people’s homes seem to trickle out of their exteriors, and how the layering of materiality, from borrowed spare paint of a family member to overtly painting one’s flag on a property, are full expressions of the voices of a community speaking. The purposeful and colourful interiors of our Pasifika mothers, the bold coloured crotchet blankets on top of couches, the gilded frames of every living ancestor, cousin, aunty are in full display. This is juxtaposed against the ‘illegal house additions’ and their varying paint colours, locally sourced by a neighbour or family member who had a spare can lying about. The layering is not just of materials or relationships: underpinning these actions is a bold spirit of a community that is not a statistic. Each layer made upon their property reclaims their space, unapologetic and free.

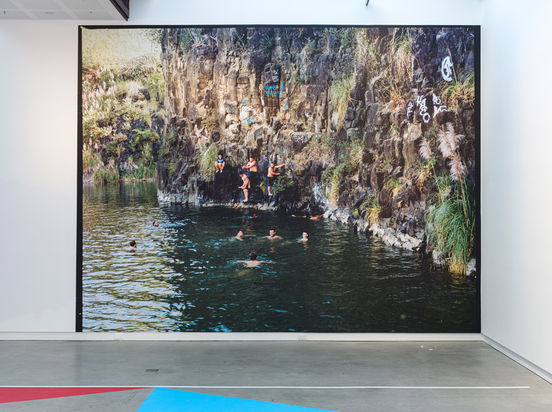

‘It is what these places say about ourselves,’ Edith says. She sees their efforts and admires their voices and their creativity. This extends to what we negotiate walking around the neighbourhood – what is public and what is private. Her work explores how the community transforms those pockets of spaces that are considered private into public use. In her latest piece, she looks into a privately owned quarry that straddles the line of public, communal space and private exploitation. As Edith speaks to her process, she is grounded not only in her sense of place but also in the importance of service to it.

Where does hostile architecture sit in this conversation? As Edith uncovers intimate moments in Rānui that negotiate the built environment, she expresses that the hostility is not in her practice but in the privatisation that prohibits access in the community: the removal of a bench in a public train stop that ‘encouraged unruly behaviour’, the public use of a quarry that is private. Privatisation is hostile in a community that chooses to be unapologetic. As council and private owners preside over spaces, the fabric of those spaces begins to feel separate to the memories we hold of them. This sits in contrast to our homes – as additive collages of inheritance and communal offerings, in all their bright hues, they feel loved and lived in.

‘Hostile as a word I like; hostile I feel connected to as an emotion.’ Edith recognises hostility as a cultural norm of navigating life as a Samoan woman. There is a familiarity of that emotion through a lived-in experience of her place.

They are two foreign terms to put together and Architecture feels even more foreign, the idea of architecture. I have been educated to understand it, but it is not something I can find in my immediate circle, or something people are bringing up in our drink ups.

Edith speaks to how architecture is still a privileged space that is limited in access to those with a level of education to assist in that understanding. Even through that understanding, Edith acknowledges how that level of work is unattainable to the community and herself. Architecture feels like things done to people. This opinion is not uncommon within the Pasifika community and is unfortunately a prime example of how architecture’s privilege illustrates the broken link of accessibility and visibility to our minority communities.

It is in spite of those faces of hostility in spaces, in architecture and many other situations, the Pasifika and Māori community continue to achieve and thrive. By claiming space, the emboldened spirit of the community is a celebration of reclamation and identity. Hostility in architecture is an agitated state but in Edith’s practice she frames her work by challenging those norms in her every day, platforming the strong currents of expression in her place that fight that repressive state of conformity, caught by the humility of her work.

As Edith’s young daughter stands her ground against the requests of high schoolers and in turn adults, it illustrates that we have a chance to learn from that unapologetic reply of ‘you could never’.

You could never repress my voice.

You could never take from how I see my world.

You could never understand the power of my belonging.

You could never negotiate how I feel.

--

Edith Amituanai is a New Zealand-born Sāmoan photographer working from the suburb of Rānui in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. She has exhibited extensively in galleries and museums across Aotearoa and internationally in Australia, Austria, Taiwan, Germany and Canada. In 2008 she was nominated for the Walters Prize for her series Dejeuner that examined a new Pacific diaspora, expatriate New Zealand Sāmoan rugby players living and working in Europe. Her artwork is held in national collections including Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū and Govett-Brewster Art Gallery.

Icao Tiseli is an architecture graduate with Jasmax. She works on projects across education, civic and heritage sectors and was part of the team that worked on the Te Ao Mārama project at Auckland Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira. Through her practice she has been exploring visibility and creativity both for personal and collective development.

--

This text is republished from Toro Whakaara: Responses to our built environment, a publication produced by Objectspace to accompany an exhibition of the same name. The publication is edited by Tessa Forde, and copy-edited by Anna Hodge.

Edith Amituanai, The Quarry, 2021. Installation view in Toro Whakaara at CoCA Toi Moroki, Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Edith Amituanai, Car on stilts, 2021

Edith Amituanai, WPV Pātaka, 2021

Edith Amituanai, Marinich Drive short cut, 2021