-

Author

Gina Hochstein -

Date

11 Feb 2022

Essay

Toro Whakaara: Raphaela Rose

The public toilet can be viewed as a functional piece of architecture where social, historical, sexual and cultural implications directly impact everyone. It is a space that negotiates being a small, private and personal room within the fabric of a public environment. Public toilets as architecture incorporate an aesthetic similar to that of the domestic, to reduce the idea of being seen and the embarrassment of going to the toilet publicly. There is tension experienced in this delineated private space, away from the public view, that seeks to give people an accepted form of privacy while performing intimate ablutions through the act of personal retreat. From occupation of these ‘discreet’ spaces, there is also a journey within a public toilet, where more than one door may need to be negotiated followed by the choice of interior walled cubicles and doors that require locking, which, in turn, becomes an act of personal concealment of the body to the public.

Auckland’s first public toilet was built in August 1863, to serve the busy wharf area and as Auckland’s suburbs began to develop, so grew the need for public toilets for the commuter’s convenience. It was only in 1910 that women were first catered for, with the Edwardian Baroque public toilets on Grafton Road, which doubled as a tram stop on the corner of Symonds Street and Grafton Bridge. Though a dedicated, female-only space, users still had to navigate and squeeze past sheltering commuters to avail themselves of the facilities until the entrance was moved to the side of the building.

Up until this point, if a woman wanted to use a toilet in the city, she would have had limited options – either visiting the train station, the public library (now Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki) or Smith & Caughey’s. With the emergence of public conveniences, women now had more agency over their freedom of movement.

Underground or subterranean toilets were built for a rapidly expanding populace and were thought to be advantageous by having little impact on the streetscape, often placed beneath busy street intersections. They were also a response to social culture at the time, through the need to be circumspect with bodily matters. However, there was a darker, more sexually charged side to below-ground public toilets. With little public surveillance, the location and design of these spaces gave rise to illicit acts and unsafe behaviour that was able to be concealed. A negative and tense stigma about such spaces arose within cultural consciousness from the reporting of and imprisonment for violence and sexual acts that took place there. From 1942, as a response to continuing subterranean activities of an illegal nature, underground toilets were no longer built.

As a result of the connotations attached to the typology of a public toilet, many have been closed and now are inaccessible. In failing to provide easily accessible facilities local authorities create inequity and a signal that personal needs are neither valued nor belong in the public realm. These spaces, by their design, have shaped our cities as unsafe spaces and are experienced as ‘hostile architecture’.

Rose responds to the idea of ‘hostile architecture’ through examining the intangible nature of the subterranean, decayed and dismantled structures of the public toilet in central Tāmaki Makaurau. She addresses the inequity of social access of these spaces by use of spatial hierarchies in her installations, with layering of abstract drawings, light and colour. The work examines the specific architectonic architectural elements within public toilet spaces – such as screens, stairs and glass bricks – and the ways in which they employ light, materiality and form to explore the tension between the visible, material manifestation of architecture and the ramifications of the invisible forced behaviours it curtails, causing widerrippling political effect. Four public toilets are distilled into thought-provoking and compelling works that communicate social and cultural implications of who has the agency to inhabit this space.

Rose’s current work is a development of ideas and processes explored in her previous lightbox work New Nightclub for Courtenay Place (2017), in collaboration with Susana Torre and artist collective lightreading. That project used stories of the women who shaped Wellington’s nightlife, creating a fictitious, new and socially progressive nightclub through atmospheres, colours and lighting, and suggesting that nightlife has the potential to empower counter-cultural movements and social change. Rose’s personal practice of mediating art and architecture brings a sophisticated enquiry into complex notions that a public space within the urban environment has greater meaning. By exposing the tension of societal norms, she challenges modern urban conditions through her visual aesthetics and articulates the transformative and undeniably transgressive concepts in these large-scale lightboxes.

—

Raphaela Rose is an architect based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. She has recently launched her own transdisciplinary design practice AHHA with four other collaborators. She previously worked for RTA Studio, having returned to Aotearoa New Zealand after a period of practice in Spain and then New York. Rose aims to push the boundaries on other ways of doing architecture. Her interests lie in the social implications of space specifically in relation to gender and politics. Her work ranges from speculative projects through to design and build, and more traditional built forms of architecture. Rose’s work has been exhibited in both Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally.

Gina Hochstein is a University of Auckland School of Architecture and Planning graduate, with a Master of Architecture (Professional) and Master of Heritage Conservation degree. She is now engaged in a PhD by creative practice exploring abstraction of gender within the domestic realm during modernism in Titirangi, as well as teaching design and managing master’s theses.

—

This text is republished from Toro Whakaara: Responses to our built environment, a publication produced by Objectspace to accompany an exhibition of the same name. The publication is edited by Tessa Forde, and copy-edited by Anna Hodge.

(above & below) Raphaela Rosa, The light that glistens so darkly- four toilets that stand or once existed across Tāmaki Makaurau, 2021. Photography by Seb Charles.

Toilets, Durham Street. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. Reference: 314-4-8A.

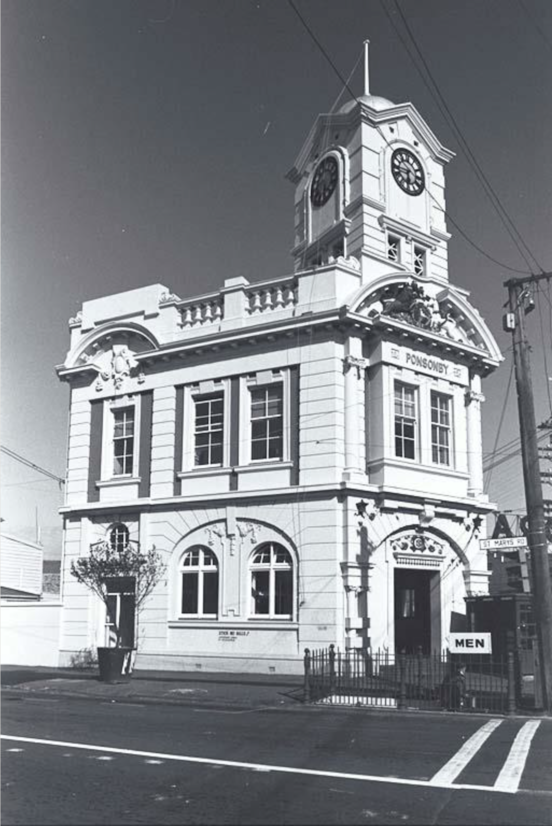

Three Lamps. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. Reference: 435-B4-196A.

Public toilets with posters on back door. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. Reference: 580-380.