-

Author

Tanya White -

Date

22 Dec 2022

Essay

Wānangatia Te Wahakura: Weaving Wellbeing for Mokopuna and Whānau

Republished from Embodied Knowledge, Issue 3 of The Vessel

In this extensive text by kairaranga (weaver) Tanya White we are introduced to the wahakura, a woven bassinet for infants made from harakeke, a native plant of Aotearoa New Zealand. The wahakura are vessels of wellbeing, providing safe sleeping spaces for small children. The article presents a case study of raranga wahakura (the practice of making a woven bassinet). It is an articulation of raranga (weaving) epistemology from a weaver’s perspective.

Introduction

Wahakura (woven bassinets) are vessels of wellbeing, providing safe sleeping spaces that give tangible form to applications and processes of tikanga pā harakeke (protocols for using and tending to flax). As such, they are a woven manifestation of whakapapa (genealogy) and an embodiment of mana (prestige), mauri (life force) and tapu (the sacred), emanating from the pā harakeke (flax bush), a site of significance, a wāhi tapu (sacred place) and a repository of taonga raranga (treasured weaving). This essay presents a case study of raranga wahakura (practice of making a woven bassinet). It is an articulation of raranga (weaving) epistemology from a weaver’s perspective. It works to highlight the essentiality that, relationships with Papatūānuku (earth Mother) have towards achieving hauora (health) outcomes for mokopuna (grandchildren). Tikanga pā harakeke provides a tangible model of practice for oranga whānau (wellbeing of the family), serving as a point of access for whānau (family) to connect with Te Ao Māori (the Māori world), and its fundamental nature as a ‘woven universe’.

A Weaver’s Perspective

I am a kairaranga, a weaver, a grandmother, a descendant, and a mokopuna (grandchild) from many. The wahakura I weave are the workings of many. They are data that evidence a woven network of whakapapa (genealogy) relationships to whānau (family), tūpuna (ancestors), Atua (ancestors of influence), to Papatūānuku (earth Mother) and te taiao (the natural world).

Waiomio is the awa.

Miria is the marae.

Te Rapunga is the whare tūpuna.

Hahaunga is the whare kai.

Wairere is the urupā.

Hineāmaru is the tupuna wahine (1)

It was on my mother’s marae (tribal meeting ground) that I first saw how people are woven together, to each other, to the whenua (land) and to tūpuna (ancestors).

When I was eleven there was a reunion at Miria marae for the descendants of Poraumati Riki Reihana and Huia Maihi Kawiti, my mother’s paternal grandparents. I remember sitting in Te Rapunga, our whare kaumātua (older building of the marae complex), and being in awe of the reams of brown paper covering the walls of our meeting house. Upon this brown paper was written a meticulous account of our whakapapa connections, to each other and to the wider groupings of Ngāti Hineāmaru (tribal group from the north of Aotearoa New Zealand). I sat for hours, carefully writing with pencil the ancestor names from the paper on the wall into a book of remembrance my parents had given to me. Rows and columns of names were grouped according to the specific branches from the family tree which they represented. Interspersed with horizontal and vertical penned lines, the words, the names, the tūpuna (ancestors) were woven, just like the photos of loved ancestors carefully grouped by the aunties and presented on the walls. They exhibited a raranga (weaving) pattern repeating itself in various ways around the walls of the whare (house), giving a sense of movement and continuum. This was my first conscious witnessing, as an eleven-year-old, of the whakapapa grid.(2) It is upon these experiences within Te Rapunga that my understanding of whakapapa is planted.

Te Kahu o Te Ao: The epistemological fabric of raranga and weaving a worldview

The universe is woven. Raranga (weaving) epistemology is grounded in whakapapa (genealogy) relationships to Papatūānuku (earth Mother), to the natural environment, and to the very fabric of the universe. The writings of Rev. Māori Marsden state that “The whare wānanga (place of higher learning) sees and interprets the world as a kahu, a fabric comprising a fabulous matrix of energies; rhythmical patterns of pure energy, woven together…” (Marsden, 2003, p. xiii). After the Second World War, Māori Marsden returned to the whare wānanga and was questioned by the elders about his war experiences.(3) One of the elders asked him to explain the difference between an atom bomb and an explosive bomb. Marsden recalled Einstein’s concept of the real world behind the natural world as being comprised of ‘rhythmical patterns of pure energy’. Essentially, the same as what Māori refer to as ‘hihiri’ (pure energy). Marsden relates the following conversation and provides an English translation in his essay on Kaitiakitanga.

Ka tū mai a Toki, ka kī, “E mea ana koe, kua oti i ngā tohunga Pākehā te hahae i te kahu o te Ao?”

Ka kī atu au, “Ki taku mohio, ae.”

Ka kī mai a Toki, “E taea e rātou te tuitui?”

Ka kī atu au, “Ki taku mohio, kao.” (p. xiii)

Do you mean to tell me that the Pākehā scientists (tohunga Pākehā) have managed to rend the fabric (kahu) of the universe?”

I said, “Yes.”

“But do they know how to sew (tuitui) it back together again?”“No!

(Marsden, 2003, p. xiii)

Io (supreme being) is the grandmaster weaver, sewing the universe together into a magnificent woven fabric of cosmological purpose and design, Te Kahu o te Ao (the fabric of the universe). Our place within this woven fabric is displayed in rituals of encounter upon the marae (tribal meeting ground), as woven whakapapa relationships between people and cosmological divine order are demonstrated.

“Wahakura are a woven manifestation of whakapapa” – Tanya White

The wahakura is a taonga (treasure) that articulates fundamental whakapapa relationships between the weaver, the whenua (land), and the wider whānau (family) and hapori (community). There are links and intrinsic relationships held by a woven vessel.(4) Links to harakeke (flax) and Papatūānuku (earth Mother), where rituals are observed. Links to the kairaranga (weaver), the one who gathered, worked and caressed the leaves of harakeke to give shape and design. Links to the mokopuna (grandchildren) when the wahakura is passed to whānau. And links to tūpuna (ancestors) and Atua (ancestors of influence) in applications of tikanga (customs) that frame raranga (weaving) processes. Whakapapa, which is all of our whanaungatanga (relationships) is the foundation of our being. It encompasses all relationships we experience. Not only the relationships between people, but also connections to the whenua (land), moana (sea), celestial bodies, and to Atua. It is the connective tissue linking all things from the infinite cosmos to microcosmic organisms.

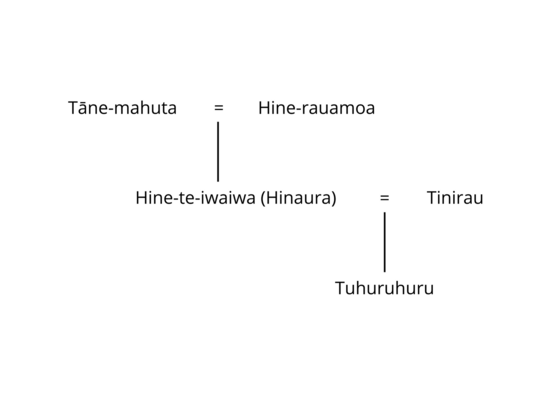

Hineteiwaiwa

There are numerous kaitiaki (guardians) associated with raranga, including Hine-te-iwaiwa, Huna, and Rukutia (Harrison, Te Kanawa, & Higgins, 2004). Kaitiaki relationships and their significance to mahi raranga (weaving processes) are revealed and retained in kōrero pūrākau (storytelling), from which we can reflect upon and understand our shared experiences.

Hine-te-iwaiwa is the daughter of Tāne-mahuta and Hine-rauamoa.

Pūrākau

Hineteiwaiwa, who was once known as Hinaura, is the kaitiaki (guardian) of the Whare Pora (house of weaving), and childbirth (Jenkins & Harte, 2011). Her story is one of transformation. It speaks of courage, strength, and resilience through adversity.

Hinaura, sister to Māui5, had married Irawaru, who was transformed into a dog by Māui tikitiki. The grieving Hinaura threw herself into the sea, and was washed ashore at the home of Tinirau, whom she eventually married.

Hinaura and Tinirau had a child, Tūhuruhuru. They were very happy together for a time, living at Tinirau’s kainga (home). Until Tinirau hit Hinaura, which caused her to leave, taking her son and returning to her whānau (family) village.

After months of Tinirau’s pleading, Hinaura returned to his kainga (home) with Tūhuruhuru. They were again happy until one day Tinirau found another woman. Hinaura objected, so Tinirau imprisoned her behind a wall of magic whale rib bones. Hinaura was angered and called to her brother Maui-mua for assistance. Maui changed himself into the form of a rupe (pigeon) so that Hinaura could ride on the pigeon’s back and escape her prison.

Hinaura gathered courage and decided to move on with her life. To mark the event, she changed her name to Hineteiwaiwa and became patroness of the powers and responsibilities of women in relation to whānau (family) and the arts. She protects and defends women in their work, especially in hapūtanga (pregnancy) and the arts of the Whare Pora (house of weaving). Her pao (chant) is used during birthing to assist safe passage for the newborn infant.

Tikanga Pā Harakeke

A weaver sustains connections to Papatūānuku (earth Mother) through tikanga (customs), that sustains relationships to te taiao (the natural world) and the gathering of materials in a sustainable way.

Tikanga associated with the gathering of harakeke (flax) is expressed in the following well known whakatauākī (significant saying) composed by Te Aupouri kuia rangatira (female elder of importance in a tribal group), Meri Ngaroto, in the early 19th century.(6)

Hutia te rito o te harakeke

Kei hea te Komako e ko?

Kī mai ki ahau

He aha te mea nui o te ao?

Maku e kī atu

He tangata, he tangata, he tangata.

If you pluck out the heart, the new shoot of the harakeke

Where will the Bellbird sing?

If you ask me

What is of most importance in this world?

I will answer

It is the new shoot, the mokopuna, it is people.

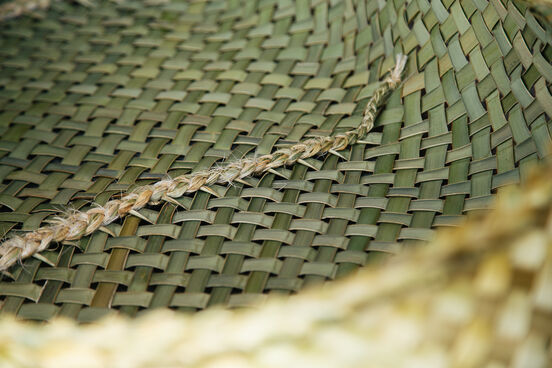

Ngaroto draws upon the metaphor of the pā harakeke (flax bush) as a representation of a thriving community and whānau (family). The long, sword-shaped leaves of the harakeke (flax) are joined at their base in the shape of a fan. Each fan represents a whānau. The rito (central flax shoot) is the central shoot and is considered to be the heart of the pā harakeke. It represents the child, pēpi (baby), or mokopuna (grandchild) of the harakeke whānau (flax bush family). It is the new growth.

The paramount objective of tikanga pā harakeke (protocols for using and tending to flax) is to protect the rito (central flax shoot), because the rito ensures the continuation and longevity of the whānau (family). The leaves on either side of the rito are mātua (parent) leaves, also known as awhi rito (support shoots) because they embrace and nurture the rito. Outer leaves are referred to as tūpuna (ancestors). It is these outer leaves which are generally harvested for weaving purposes. If the central shoot, the heart, or the rito of the harakeke plant is plucked out, the wellbeing of the harakeke whānau becomes severely impaired. Without new growth, or children to sustain its development, a whānau will eventually die. Within this whakatauākī, Ngaroto’s plea is asking us to consider not just those who are present, but all those potential descending generations who are connected to them. Those yet to be born.

As an ecological model, the whakatauākī (significant saying) speaks about our responsibilities towards care and protection of the whānau harakeke. It is a direct reference to the responsibilities of people to interact with each other and with the environment in a careful and sustainable way. It speaks about manaakitanga (generosity) and kaitiakitanga (guardianship) and reminds us that our actions will have far reaching consequences, spanning generations.

Wahakura

The first wahakura I wove was for my daughter Maiarangi, born in 1993. I was a student of Kahutoi Te Kanawa and part of the weaving programme at Puukenga, Te Whare Wānanga o Wairaka, Unitec. Hundreds of fine width whenu (harakeke strands) were used. The design was whakatū (upright) weave, with three whiri (plaits) at its foundation. The harakeke was gathered from Waiatarua at the base of Maungarei maunga (mountain). We didn’t call it wahakura at that time. It was a waka (vessel), or pēpi moenga (baby bed). The components were and are the same. Harakeke, or kiekie (vine), and three whiri at the base, to provide integrity and strength in their foundations.

“As the whenu (strands) are woven together, there is a plaiting and weaving of whakapapaconnections. The mauri (life force) of the whenua (land) integrates into the next phase of developmentand the base of the wahakura begins to develop. There is a sharing of knowledge as interestedparticipants contribute and participate in the shaping of kōrero (discussion). The mauri of peoplepresent becomes a part of the wahakura.” (White, 2017a, p. 51)

From the three-whiri base, connections are solidified, allowing for further development as the sides and embracing body of the wahakura tinana (bassinet form) are formed.

The Wahakura kaupapa (initiative) emerges from the rangahau (research) and work of Dr David Tipene-Leach in the field of Sudden Unexplained Death in Infancy (SUDI) prevention and Safe Sleeping practices. It is a return to a traditional Māori way of sleeping babies that promotes breastfeeding and bonding with baby. Dr Tipene-Leach, as part of the Wahakura Project (Tipene-Leach, 2007), notes that Best (1975) records a bassinet-like structure in pre-European times called a porokaraka. “A flax [harakeke] cradle that was slung from a tree or from the rafters of the wharepuni (sleeping house) or wherever the mother went” (Tipene-Leach, 2007, p. 6). It was also noted that kuia (female elder) involved in the 2007 Wahakura Project spoke of babies being laid in kete kumara (basket for sweet potato) to sleep while the parents tended their gardens. The Wahakura Project (Tipene-Leach, 2007) developed a life-saving taonga (treasure) that was built upon ancient traditions and previous experiences of kairaranga (weaver).

He Wahakura, He Wānanga

Every weaving of a wahakura is a wānanga (forum). A learning journey that is specific to the creation of that particular taonga (treasure). There is a learning that happens, in the relationships between the weaver, the whenua (land), and the whānau (family). It is an opportunity to take notice of ngā tohu o te taiao, the signs and indicators from the whenua, from the environment. It is these indicators that will guide processes around the timing of when to gather the harakeke, which pā harakeke to gather from, how the harakeke will be prepared, and who will participate in the weaving. Ngā tohu o te pā harakeke, signs and indicators from the pā harakeke are unique on any given day. They reveal relationships to the whenua and can provide understandings about the conditions of whakapapa (genealogy) from which the wahakura emerges.

In 2017 Ngāti Whātua ki Ōrākei (tribal group from central Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland) came to Te Noho Kotahitanga marae (meeting ground) at Unitec, to receive a group of wahakura that had been woven from Rangimarie pā harakeke (the flax garden based at Te Noho Kotahitanga marae, Unitec). While in the whare Ngākau Māhaki (meeting house), we were able to share experiences and connections to the wahakura kaupapa (initiative). Beronia (master weaver) shared a vision of ngā waka o ngā mokopuna. “I’m seeing all the mokopuna in these waka (wahakura) rowing together, and the wake behind them, that is the ancestors.” Sariah (Weaving Waiora facilitator)(7) expressed that the wahakura were taonga tuku iho no ō mātou tūpuna (treasured cultural heritage handed down from our ancestors). “We’re lucky to have that knowledge, skill, and expertise still available for us. Not just for us, for our mokopuna.”

Whaea Virginia (kuia, female elder of Weaving Waiora) stated that;As wāhine (women), it is intrinsically within us. We have the knowledge to be able to share to all our hapū māmā (expectant mothers), to all our mokopuna (grandchildren). To be able to make them safe through this kaupapa (initiative). As each one has shared what they have seen and experienced with the wahakura, I keep seeing that we can keep our babies safe. Keep them close to us, and keep them safe. And we can pass that kaupapa and knowledge on, into our generations. (White, 2017b)

Matua Toko (Weaving Waiora and Ngāti Whātua kaumātua, elder of status) began by presenting a cooking analogy, and then returned our focus to connections to Papatūānuku (earth Mother);The only time my children enjoy my cooking is when I enjoy cooking it. When I take my time to cook the meal, I cook it with my heart. Same with the weaving of the wahakura. Every weaver will weave in their own time, at their own pace, and they’re getting their own therapy and rongoā (remedy), their own mirimiri (massage), and they’re weaving their own kōrero (discussion) into every binding of the wahakura.

You might say that this is the completed weaving from the weaver, yet you still have the weaving with the pēpi (baby) inside the wahakura. There is a weave that the pēpi has around the mother and the father, and again with all the siblings. And then you have the weaving of the whānau (family).

This is the many faces of the weave. It is not just what is in front of us. It is what is inside, and before it. What it actually takes to get the muka (flax fibre). What it takes to grow the harakeke (flax). And again, it all comes back to Papatūānuku. The intent belongs with Papatūānuku. Even for the men. (White, 2017b)

Mokopuna

Mokopuna (grandchildren) are the rito (central young shoot), they are the new growth and the heart of our pā harakeke (flax bush), our whānau (family) and communities. They grow between the embrace of awhi rito (support shoots), parents, grandparents and the wider whānau. Mokopuna are our maintenance plan. They carry our mātauranga pītau ira (DNA knowledge), and our aspirations and ways of being are reflected in them. The wahakura has become part of our legacy left for them.

“A generation now exists who do not know the times before the wahakura. It is as if the wahakura has always been here and it is woven into the fabric of our family lives.” Tipene-Leach (Faiers, Rhind-Wiri, & Selby-Law, 2019)

We are all mokopuna. Descendants of ancestors, connected to whakapapa layers that are woven through and from Te Kahu o Te Ao, the woven fabric of the universe.

The mokopuna (grandchild) pictured is Pikia. Her whānau (family) gathered together to wānanga (forum) at Te Noho Kotahitanga marae in 2017, in preparation for her birthing into Te Ao Mārama (the world of light). Her nannies, aunties, māmā (mum) and pāpā (dad) were there. Together they gathered and prepared harakeke (flax), and wove with their hands, kōrero (discussion), laughter and aroha (love), her wahakura. Tipu mai, mokopuna mai e Pikia.

The process of weaving the wahakura supports the wellbeing of whānau (family), and whenua (land). Expressions of oranga tangata (wellbeing of the people), oranga whenua (wellbeing of the land) are conveyed in Ngā Whenu o te Wahakura (Faiers, Rhind-Wiri, & Selby-Law, 2019). “From Te Ao Māori (Māori world) perspective, the land and the plants sourced from it intrinsically sustain and nourish the wellbeing of whānau and communities,” (p. 7). Hāpai te Hauora continues to relate the movement and flow of process from whenua to mokopuna (grandchildren). “Wahakura are made of harakeke (flax), and the process from its inception at the pā harakeke (flax bush), through to the weaving of each whenu (strand), through to the practical application of the wahakura, inherently sustains the wellbeing of mokopuna” (Faiers, Rhind-Wiri, & Selby-Law, 2019, p. 7).

Every whenu (strand) of the wahakura, every weave, every interrelationship threaded through, over and under, is a pathway of woven whakapapa (genealogy), seeded in sustainable practices, tikanga (customs), that ground us to Papatūānuku (mother Earth). Wahakura articulate a synthesis of mauri (life force). The mauri of Papatūānuku, the mauri of the kairaranga (weaver), and the mauri of the whānau and mokopuna. Wahakura, as the name suggests, waha (gateway, entrance, opening), kura (sacred knowledge), are a point of access to mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) and the treasured knowledge handed down from the ancestors. They provide an opportunity for whānau to connect with Te Ao Māori (the Māori world) through tikanga pā harakeke (protocols for using and tending to flax) where oranga mokopuna (wellbeing of the grandchild) is central and essential to oranga whānau (wellbeing of the family) and whenua (land).

Wahakura are waka o ngā mokopuna, waka oranga (vessels of wellbeing) because they house and embrace ngā taonga tuku iho (treasures handed down), the wisdom of the ancestors, while protecting and cherishing the new generation.

Raranga Waiora

Raranga Mauri

Raranga Whakapapa

Raranga Wahakura

—

Footnotes:

1. From a Māori worldview, pepeha (tribal sayings) are used to introduce your connections by reciting important ancestral links to significant people and places.

2. Dr Pat Hohepa, cited in (Henare, Petrie, & Puckey, He Whenua Rangatira : Northern Tribal Landscape Overview, 2009, p. 131) talks about the organised arrangement of ancestors. “It is the fixed chart view of the item and the arrangement. You are the item, they are the arrangement. It is a static diagram.”

3. They convened in the Hokianga (located on the west coast of the north island, Aotearoa New Zealand)

4. Pa Henare Tate outlines these links in the introduction to He Kete He Korero (Maihi & Lander, 2005)

5. Hinaura is also known as a cousin to Maui.

6. (Henare, Puckey, & Nicholson, 2011) (Henare, 1995) (Quince, 1999)

7. Weaving Waiora is a kaupapa Māori parenting, pregnancy, and birthing programme for whānau.

Source chapter Raranga Waha Kura appears in the book Tiakina Te Pā Harakeke, 2022.

References:

Best, E. (1975). The Whare Kohanga (The Nest House) and its Lore. Wellington, New Zealand: A R Shearer, Government Printer.

Faiers, N., Rhind-Wiri, H., & Selby-Law, F. (2019). Ngā Whenu o te Wahakura : The Many Strands of Wahakura. The National SUDI Prevention Coordination Service at Hāpai te Hauora. Retrieved from this website.

Harrison, P., Te Kanawa, K., & Higgins, R. (2004). Ngā Mahi Toi : The Arts. In T. M. Ka'ai, J. C. Moorfield, M. Reilly, & S. Mosely (Eds.), Ki te Whaiao : An Introduction to Māori Culture and Society (pp. 116-132). Auckland, New Zealand: Pearson New Zealand.

Henare, M. (1995). Te Tiriti, te tangata, te whānau : The Treaty, the human person, the family. Rights and Responsibilities : Papers from the International Year of the Family Symposium on Rights and Responsibilities of the Family, Wellington, October 14-16.

Henare, M., Petrie, H., & Puckey, A. (2009). He Whenua Rangatira : Northern Tribal Landscape Overview. Wellington, New Zealand: Crown Forestry Rental Trust.

Henare, M., Puckey, A., & Nicholson, A. (2011). He ara hou : The pathway forward : Getting it right for New Zealand's Māori and Pasifika children. Wellington, New Zealand: He Mana tō ia Tamaiti : Every Child Counts. Auckland, New Zealand : University of Auckland. Retrieved from this website.

Jenkins, K., & Harte, H. (2011). Traditional Māori Parenting : An Historical Review of Literature of Traditional Māori Child Rearing Practices in Pre-European Times. Auckland, New Zealand: Te Kahui Mana Ririki.

Maihi, T. T., & Lander, M. (2005). He Kete He Korero: Every Kete Has a Story. Auckland, New Zealand: Reed.

Marsden, M. (2003). The Woven Universe : Selected Writings of Rev. Māori Marsden. (T. A. Royal, Ed.) Otaki, New Zealand: Estate of Rev. Māori Marsden.

Quince, K. (1999). Māori Disputes and Their Resolution. In P. Spiller (Ed.), Dispute Resolution in New Zealand (pp. 256-294). Auckland, New Zealand: Oxford University Press.Tipene-Leach, D. (2007). The Wahakura : The Safe Bed-Sharing Project. Retrieved fromthis website.

White, T. (2017a). Mana Mokopuna : Mai i te Waharoa ki te Wahakura : Activating Sacred Potential Through Raranga and Tikanga Pā Harakeke. (Master's thesis) Te Whare Wānanga o Wairaka, Unitec Institute of Technology, New Zealand. Retrieved from this website.

White, T. (2017b). Mana Mokopuna : From Waharoa to Wahakura : Applications of Raranga and Tikanga Pā Harakeke for the Protection of Papatūānuku (Earth Mother) and Mokopuna. Transcript of Video Presentation, World Indigenous Peoples Conference on Education, Toronto.

—

This text was originally commissioned for and published in Issue 3 of The Vessel, an online magazine about crafts and material culture published by Norwegian Crafts. Titled ‘Embodied Knowledge’, this issue explores the Influence of Whakapapa and Maadtoe jah Maahtoe and is edited by Jasmine Te Hira, Carola Grahn and Objectspace Deputy Director Zoe Black.

Wahakura at Te Noho Kotahitanga Marae. Photograph by Emily Parr.

Tanya White weaving with harakeke at Ngākau Māhaki Wharenui. Photograph by Emily Parr.

Tanya White weaving with harakeke at Ngākau Māhaki Wharenui. Photograph by Emily Parr.

Whakapapa of Hine-te-iwaiwa.

Harakeke. Photograph by Emily Parr.

Inside structure of the woven wahakura by Tanya White. Photograph by Emily Parr.

Wharenui Ngākau Māhaki from Rangimarie Pā Harakeke. Photograph by Emily Parr.

Pēpi Pikia in her woven world, her wahakura woven by māmā Mani, pāpā Hayden and whānau. Photo courtesy of Tanya White.